Growing up as a girl in the ’50s and ’60s, Debra “Debbie” Powers was told a lot of things about herself that she knew, and would later prove, to be untrue.

Expectations that she would always be polite, quiet and “ladylike” were enforced. Slacks or jeans weren’t feminine enough — she needed to wear a dress or skirt. She even had a teacher tell her in elementary school that no one would want to marry her because she was “too aggressive and competitive.”

The most difficult standard for Powers to conform to was that it was not culturally appropriate for her to enjoy sports of any kind. Growing up around three brothers and developing a love of basketball early in life, her exclusion from sports was disheartening and confusing.

“I could not figure out why, why I couldn’t play in sports … I mean, I loved it so much, I didn’t understand why they said I couldn’t play, even on any of the boys teams,” Powers said. “I figured, as I got older, it was a cultural view.

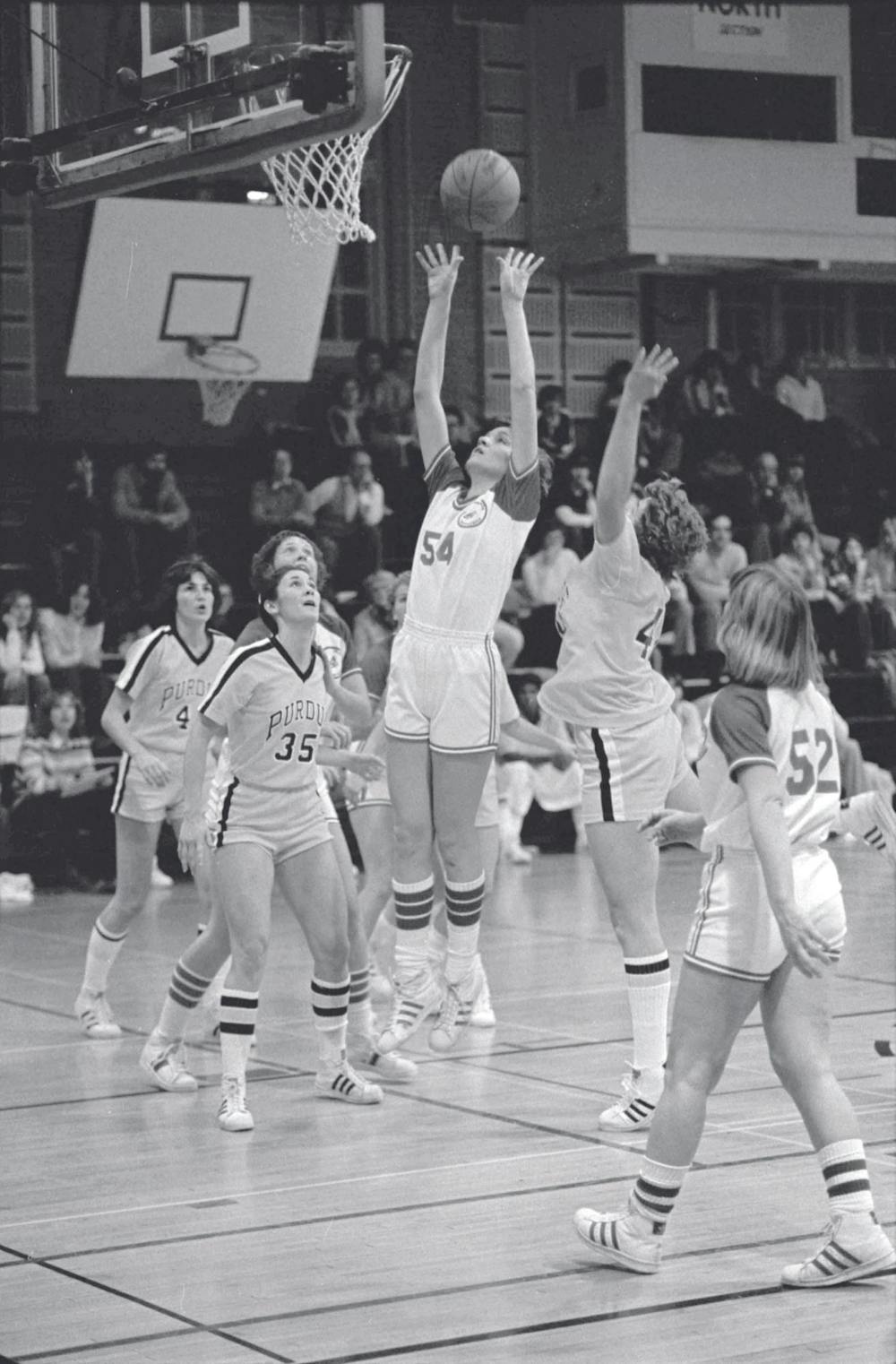

Powers, head coach for Ball State’s women’s basketball during the 1976 to 1982 seasons, didn’t let any of these expectations stop her from pursuing her passion. She practiced in skirts and dresses on the playground and went home to play with her brothers and friends in her driveway.

She didn’t know it at the time, but Powers would eventually join the fight to advocate for women in sports and prove to people that her “aggression” and competitive nature could be utilized as positives.

Ball State’s first female athletic director holds up the women’s basketball schedule and team photo March 17, 1983 in Muncie, Ind. Seger said transitioning Ball State’s programs to comply with Title IX was a slow process. BSU Archives, Photo Provided

Women on the outside

Throughout Powers’ childhood, she continued to watch her male peers be encouraged while she was reprimanded for participating in sports.

It wasn’t until Title IX was implemented in 1972, when Powers was in college, that it became somewhat accepted for girls to be involved in any sport.

Title IX is a federal civil rights law stating educational programs and activities that receive federal funding can’t deny anyone benefits or discriminate against people because of their sex, according to the U.S. Department of Education.

Andrea “Andi” Seger also played a big role in advocating for women in sports in Indiana. She started as an assistant athletic trainer at Ball State before being promoted to the school’s women’s athletic director in 1983. After 12 years in that position, she became Ball State’s first female athletic director when women’s and men’s athletic departments were combined into one at Ball State.

She had a similar experience to Powers growing up, watching her male peers be taken seriously in athletics and encouraged to join teams over her.

“They didn’t have organized sports for girls, but we had a girls club in town, and we were able to play some sports informally through that,” Seger said. “When I [got] into high school … they were just starting high school sports.”

Unlike Powers, Seger got the chance to play on teams before college. When her school introduced women’s teams she joined multiple, which led her to seek degrees in physical education and, later, athletic training.

Powers also received a degree in physical education, starting in 1969 at Indiana University (IU). Due to the discrimination she had experienced growing up, she felt early on that this was the only way she could be involved in what she loved.

“I couldn’t even be a sports writer or sports commentator or any of that kind of thing, or team owner or even have female coaches,” Powers said. “All I knew was I could be involved teaching physical education in the gym all day long and enjoying my love of sport and sharing that love with other students.”

When Powers was at IU, she saw a sign in the women’s locker room announcing women’s basketball tryouts. While thrilled when she found out she made the team, she quickly discovered it still wouldn’t be the same experience as the men.

“We had to pay for our own uniforms, our own shoes, our coach drove us in a station wagon to away games played in little, tiny cracker box gyms,” Powers said. “We didn’t get to play in the main arena, and it was because there was no law to say it had to be any equal. There was no law until 1972 when Title IX was passed.”

Despite this, Powers had experience with overcoming setbacks as a woman in sports. She took the traits she had been looked down on for her whole life to the court.

“I was strong enough in my mind. I didn’t care whatever the people thought, I didn’t care what the boys thought, I didn’t care what adults thought. I still went out and played hard wherever I was, whether it be on the playground or in the gym or anywhere,” Powers said.

Helen Martin (left) and Andrea Seger (right) at a Ball State University women’s gymnastics meet Feb. 27, 1987 in Irving Gymnasium. The meet was Cardinals versus the University of Iowa Hawks. BSU Archives, Photo Provided

‘You’re supposed to be the cheerleaders.’

The passing of Title IX was met with pushback from many Americans. Powers said the law was a step forward, but it didn’t immediately reverse the idea so deeply ingrained in society that women didn’t belong in sports.

“The boys kind of thought it was silly that girls would want to even play a sport and sweat,” Powers said. “It was still that males versus females. ‘Look at those girls, why would they do that? You’re supposed to be the cheerleaders. You’re supposed to be supporting us.’ So we always felt like second-class citizens, and we were looked down upon because we enjoyed sports.”

In 1976, the NCAA unsuccessfully sued the Secretary of the Department of Wealth, Education and Welfare arguing Title IX shouldn’t apply to sports as they aren’t directly federally funded, according to the National Association of College and University Attorneys.

“Sports was not even [directly] mentioned [in Title IX], but the NCAA and men figured out, ‘Oh my gosh, that means that will involve sports,’ and they petitioned to keep sports out of Title IX,” Powers said. “They said, ‘That’s going to ruin football. It’s going to ruin men’s sports if these girls have an opportunity.”

According to the U.S. Department of Education, three years after Title IX was passed, the government gave educational institutions a compliance deadline of three years. The transition period expired on July 21, 1978, and by the end of the month, the department had received nearly 100 complaints of discrimination in athletics against over 50 higher education institutions needing to be investigated.

Seger said Ball State received an anonymous Title IX complaint that forced the university to develop an equity plan, and it turned into a “huge fight.”

“It was a struggle, to be honest with you. Little by little we would fight for things every year, but it took a long time,” Seger said.

Starting at Ball State the year prior to Powers in 1975, Seger became very involved in faculty meetings when the issue of implementing Title IX was brought up.

“We tried to add a certain amount of money each year to the women’s program and spread it amongst the teams. When we first started women’s athletics, we were getting leftover warm up suits from the men’s programs. We didn’t even have warm up suits of our own,” Seger said. “We gradually started to increase the operating budgets.”

She said, like any other school, transitioning Ball State’s program to include women’s sports was a slow process. She said they worked each year to allocate additional dollars to women’s scholarships, but it was gradual, and they couldn’t just reallocate a large amount of money at once to even it out.

“We did a good job at Ball State of adding one or two scholarships every year for the women’s program, and so we came into equity under Title IX in the early ’90s,” Seger said. “Title IX really did play a big role in my career … It was an interesting time for me because it was a growth of our women’s athletic program during that time.”

While Seger worked to implement Title IX as an administrator, as the women’s basketball coach, Powers saw the other side of the slow progress toward equity.

“Even after I became the head coach of Ball State in 1976, it still was unfair, extremely unfair. Even at Ball State,” Powers said.

Powers’ team didn’t have to pay for their own uniforms as she did at IU, but it still wasn’t the progress many were hoping for. She said their uniforms were purchased from a sporting goods closeout sale and were blue, not Ball State’s colors, and they were shared between the women’s basketball, volleyball and softball teams.

“I was thrilled to get to be involved in a sport, but it just was not fair,” Powers said. “We did not have separate locker rooms, the girls had to buy their own shoes. We played in the old Ball Gym which was not even renovated out of a leaky roof. We didn’t even get to play on the main floor.”

The 1977 Ball State women’s basketball team pose for a photo in the locker room. Debbie Powers said the “infamous” blue uniforms were purchased from a sporting goods closeout, and they were shared between the women’s basketball, volleyball and softball teams. Debra Powers, Photo Provided

Opportunities opened for future athletes

Nearly 53 years after Title IX became a federal law, the push for equality continues. It has had a significant impact on female participation in sports, but there is still progress to be made; male athletes have a much larger pool of opportunities, and collegiate women are doubly impacted by this lack of opportunity and the correlating scholarship dollars, according to the Women’s Sports Foundation.

“Even for the next 10 to 15 years women really had to scrape to get equality,” Powers said. “[Young female athletes will] have to work a lot harder. They need to network with other female athletes and female coaches … You don't have very many women, and it's still an old boys network.”

Powers has written and published a memoir about her experience as a female athlete prior to Title IX and being a coach in the early days of implementation. She wants to encourage young female athletes to persevere and “stay with it.”

She sees how far women’s sports have come since she was a college athlete and is mesmerized by the opportunities they have now.

“I like to think I was one of the pioneers that trudged along and had to do with lesser facility and lesser opportunity,” Powers said. “I think the future is bright for women. Every little girl that wants to play soccer, softball, gymnastics, whatever sport, there is opportunity for them.”

Seger said it wasn’t until 1995 that the university vice president at the time came to her and admitted that more should have been done for the women’s athletic program.

“Forever, people have always talked about the things that athletes gain as a benefit of participating in athletics: teamwork, leadership, all of those kinds of things. Well, now women have that same opportunity,” Seger said.

She said while women still require more chances to exist in these previously male-dominated spaces, it’s no longer a question of if they deserve to be there, like when she was growing up. It’s about how to get them there and choosing between all the options women like Seger and Powers have opened up for them.

“When you’re an athlete, it doesn’t matter what sport you play, an athlete is an athlete,” Seger said. An opportunity to play sports is what’s important, and so women should have that same opportunity and those numbers of opportunities.”

Contact Ella Howell via email at ella.howell@bsu.edu.

The Daily News welcomes thoughtful discussion on all of our stories, but please keep comments civil and on-topic. Read our full guidelines here.