Katherine Hill is a second-year journalism major and writes “Cerebral Thinking” for the Daily News. Her views do not necessarily reflect those of the newspaper.

Monday: “Beloved university professor dead, leaving behind a legacy within his department”

Tuesday: “National treasure celebrity — thought to live forever — dead at 89”

Wednesday: “Breaking news: Shots fired outside local gas station”

Thursday: “Correction: Shooting has upgraded to attempted murder, according to police records”

Friday: “Campus building in lockdown, university police investigating threat”

Saturday: “Fatal plane crash in adjacent county leaves five people dead and one injured”

Sunday: “Train derailment fire just outside city leaves no survivors”

News never sleeps, synonymous with New York City, the so-called “media capital of the nation,” according to City Journal of the Manhattan Institute. It’s my job to report it, but that doesn’t make it any easier.

My family is not religious. My brother and I grew up Protestant, raised to believe in the goodness of people rather than something potentially mythological, and that if we were good people with fulfilling lives, we were doing all we could to get into Heaven.

And yet, as a third grader, I would still say my own distant prayer before bed. “Good night to everything and everyone in the world,” I’d say, burrowed underneath my covers with cupped hands.

I’ve always been an empath. It's hard not to be, having grown up in the special education system, where I was more or less dependent on the kindness of others.

I was first exposed to the magnitude of man-made cruelty during a day of expositional research in my eighth-grade English class in March 2018 when my classmates and I were tasked with poking around the Holocaust Memorial Museum website. There, I read Hitler and the Nazi regime deemed disabled and handicapped people “useless to society” and “unworthy of life.”

Feeling a lump in my throat, I went mute for the rest of the class period. I haven’t forgotten that day. I didn’t know it then, but at that moment, those words would shape me in a less-than-ideal way, imprinting into my long-term memory the longer I stared at them.

That unit has stayed with me longer than any of my academic career. I subconsciously decided I would be a writer. Tragedy strikes, but truth prevails through the immortality of the written word.

This past fall, I took an Introduction to Photographic Storytelling course in my third semester of college. As part of the curriculum, my professor taught students that empathy is a key component of journalism.

I wholeheartedly believe that.

“Telling people’s stories is a privilege and an honor,” I wrote in a bold and underlined font in my notes. However, telling people’s stories feels less like a privilege or an honor in “The Era of Fake News.”

It was hard to report the 2024 presidential election results in November of 2024. It was the reelection of a man — a convicted felon — who has openly and proudly mocked women and people with disabilities, and in the week before the election, voiced his approval for journalists to be shot at his rallies, according to the Associated Press.

But that was the news.

It was part of my job to inform my peers and Delaware County that Donald Trump would be our 47th president — the very thing I was trying to push from my memory as a 20-year-old woman with cerebral palsy studying to be a journalist.

October 2024 data from the Pew Research Center revealed young adults — 37 percent of Republicans and 38 percent of Democrats under 30 — are nearly as likely to trust social media as national news outlets.

The data also concluded trust in information from news organizations varies by age and political party, with 78 percent of Democrats expressing trust in information from national news organizations and 83 percent from local ones.

These numbers are starkly different from the 40 percent of Republicans who expressed trust in national news organizations but nearly “on par” with their trust in social media outlets for news. And 66 percent of Republicans have at least “some trust” in information from local news organizations.

“Republicans have generally become less trusting of national and local news organizations in recent years. Democrats’ views have remained more consistent over time,” according to Pew’s report summary.

There is no good journalism or thorough storytelling without human empathy, but it’s nearly impossible for me to remain empathetic and simultaneously sane when the political climate of society is disturbingly distrusting toward journalists. The vast majority of the public elected somebody who makes my job of informing and helping others harder.

My professors told stories in class of protest coverage and brought in gear journalists wore during such to protect themselves. Sitting in the front row during those lectures, I couldn’t imagine going toward danger that I, realistically, could not outrun.

I was reminded of the world’s cruelties — only this time, it seemed to me that I was a part of them.

The societal connotation that journalists do not have empathy because they ask important questions is incredibly damning to those who love and dutifully harness the craft. I would leave my classes those days and have debilitating panic attacks in my dorm room that rendered me unable to remember the basics of human functionality: dates, locations of my classes and the names of people I loved.

I had gone from experiencing panic attacks once in a blue moon to having one at least once a week for about two months; I began to view my work pessimistically and myself as a societal nuisance for taking part in a widely spat on profession.

Despite heavy emotional turmoil, I learned something invaluable: Ethical journalism creates moral dilemmas.

I cannot fix — or predict — everything as a journalist, and to hold myself to such a standard will burn me out before my passion has a chance to fully ignite. But like everyone else in this capitalistic nation, I have a job to do. Through my work, I can fix — or bring attention to — something, which could be everything to somebody.

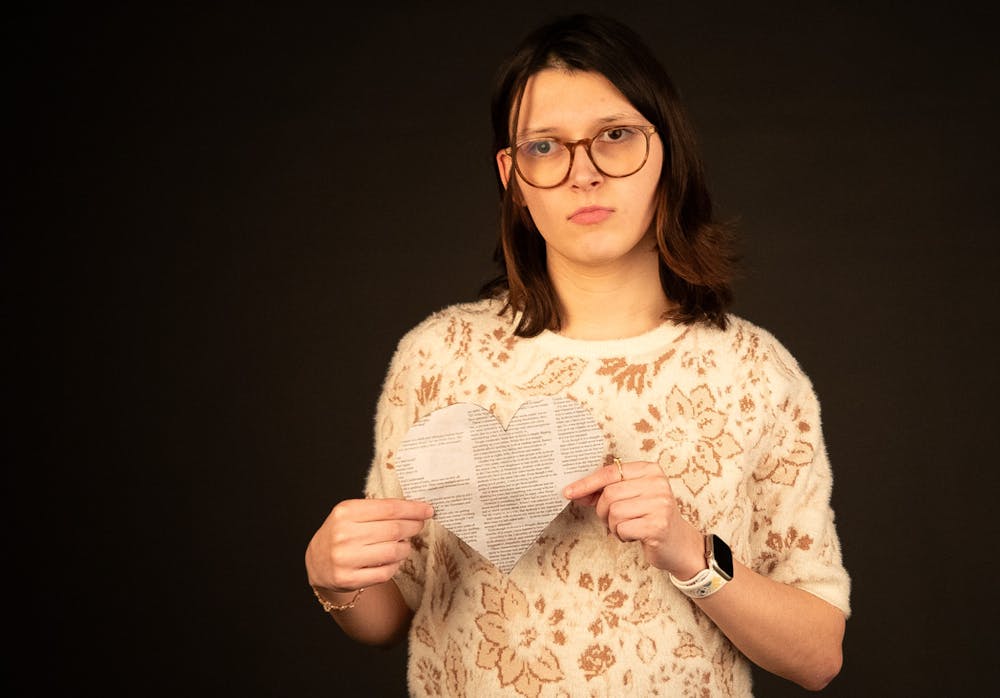

While arguably rebuilding my professional identity from the ground up, I tapped into my feminine sensibilities and became involved in my first true romantic relationship.

I was a preteen in the wake of fifth-wave feminism in 2015. My fundamental years were during Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign and the #MeToo movement the following year. I was indirectly raised to not limit myself to marriage, a white picket fence and a lifetime standing in the kitchen wearing a stained apron with a kid on each hip.

Even so, I was unsure what to believe when last fall, the career-centered education I had so desperately spent my later adolescent years clawing for seemed to be crumbling beneath my feet. What I knew about womanhood had drastically shifted when reciprocal, romantic love was introduced.

It’s possible that as I grew older, throwing myself into my studies and latching onto the prospect of a career was a way to distract myself from the humbling but inevitable realization that disability does not necessarily radiate sexual appeal.

Nothing could have prepared me for the insecurities I felt in the early days of my relationship.

I didn’t understand how somebody could fall in love with the body I had grown to hate. I’d walk the perimeter of my dorm room rug, stiffly and consciously with one foot in front of the other, unable to reverse 20 years from my cerebral cortex.

My boyfriend’s mom was my teacher in high school and three-year mentor. There is nothing I can hide from her, hardly any secret or insecurity of mine she doesn’t know. I know her, and I still tried to mask the disability at family gatherings or outings in public.

I have no excuse, but I have had people swear to my face that I’m not a burden. Their text threads, however, tell a different story.

“It’s not going to happen in my family,” my boyfriend said one November evening as we were deciding how to divide the holidays between families, and I became far too vulnerable.

“Right,” I said. “But it has happened.”

“I’m not saying it hasn’t happened,” he said. “I’m saying it’s not going to happen in my family.”

He squeezed me tightly in his arms, and while running my fingers through his hair as we laid chest-to-chest, I knew I was distrusting the wrong people — forcing the ones who loved me to explain why — instead of forcing the ones who dubbed me “incapable” to provide an explanation for their mockery.

I was no better than the vast majority of society I was pleading with to gain trust as a student journalist, actively assuming the worst in people and unable to see the goodness in the world around me.

To be loved is a necessary thing. To be loved by a family not my own is the greatest thing — something I wasn’t convinced was in my future.

Over the holiday break, I watched “It’s a Wonderful Life” for the first time with my boyfriend’s family. Coming out of a difficult semester, unsure of my path and having felt like everything I knew about myself had changed, the Frank Capra classic reminded me humans seek the same things. Nothing in life, no amount of money or career success, is more important than love; and no failure is drastic enough to deem oneself unlovable.

Contact Katherine Hill via email at katherine.hill@bsu.edu.

The Daily News welcomes thoughtful discussion on all of our stories, but please keep comments civil and on-topic. Read our full guidelines here.