Corie Hess miscarried twice before giving birth to her first son, Alex, in 2017. A year later, she found out she was pregnant again, but she lost the baby near the end of her first trimester. “It was devastating,” she said, but the trauma had just begun.

Doctors gave her medicine to initiate the miscarriage. Days later, Hess began to bleed — a lot — and it didn’t stop. She went to the hospital and was left alone in a room, bleeding, until she began to go into shock. A medical team rushed her to a trauma room, where she received two blood transfusions before going into emergency surgery.

Post-recovery, Hess began therapy to work through her grief and anxiety. “It’s taken me years to be able to get to a point where I can talk about this without breaking down,” she said.

Hess, a psychologist in Muncie, began researching about maternal mortality and birth trauma. In Indiana, mental health conditions such as depression contributed “significantly” to the number of women who died in the year after childbirth, according to the state’s Maternal Mortality Review Committee. In 2010, the committee reported that 20 moms died as a “definite or probable result” of their mental health.

Roughly 50-75% of people who have babies experience the “baby blues,” or frequent, prolonged bouts of crying, sadness and anxiety, according to the Mayo Clinic. Postpartum depression affects roughly one in seven new parents, who find themselves on highs and lows, crying, irritable and tired. They might also have feelings of guilt and anxiety that make it difficult to care for their baby or themselves.

The March of Dimes reports that depressed mothers have lower rates of breastfeeding initiation and poorer maternal and infant bonding. Their infants are more likely to exhibit developmental delays, according to the organization.

All the stats and reports swirled in her head as she talked with friends and coworkers about their experiences during and after labor. A common theme: the lack of support for families dealing with mental health problems related to pregnancy and childbirth.

A local coalition of support

In 2019, Hess founded the Muncie Maternal Mental Health Coalition, to promote and nurture the well-being of all mothers, fathers, children and families in the community. The coalition advocates for all pregnant people to have access to coordinated and comprehensive mental health screenings and services during and after pregnancy.

The coalition manages a website with information for providers and caregivers as well as links to area support groups and the Diaper Bank of Delaware County, among other resources. The site states, “You are not alone, and with help you will be well” near its mission statement to “improve mental health resources, systems and policies for new parents through community partnership, education, outreach and advocacy.”

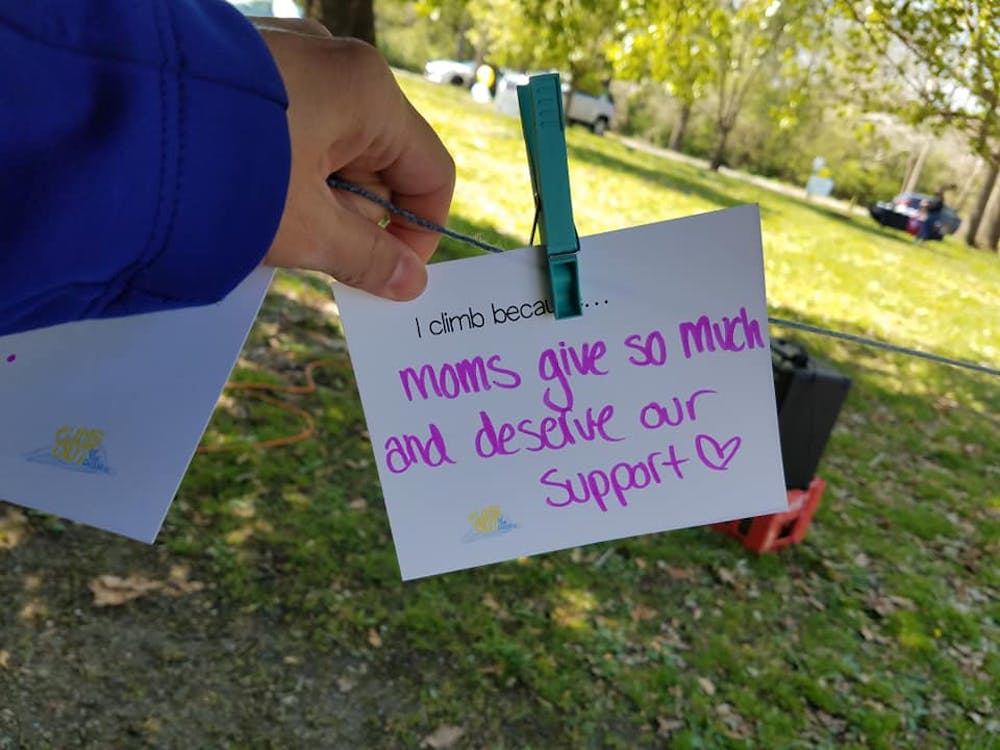

The coalition does so with the support of an active board, and a network of volunteers who help organize a range of events, including the annual Climb Out of the Darkness Walk each summer since 2021. Proceeds from the walk support efforts to help people and families living with postpartum disorders.

"Not only is it a good way to raise money, but it also creates awareness and a space for people to come together,” Hess said.

Brave individuals connect, inspire

During each walk, participants share stories. Christina Doll, an associate professor of health science at Ball State University, stood before the crowd at the 2023 walk at Westside Park in Muncie.

Doll’s son, Gabe, was born with clubbed feet, which required regular hospital visits to put his legs in casts. She was busy and tired but not depressed. Six months into parenting, she took some cold medicine to help her sleep, but it didn’t work. She felt drained and became consumed with whether her lack of sleep impacted her ability to care for Gabe.

She called her OBGYN, but she couldn’t get an appointment for months. Then a graduate student at Purdue University, Doll went to the campus health center for help. None of the therapists specialized in postpartum issues, but she saw a therapist who diagnosed her with anxiety. It wasn’t until 10 year later, when Doll saw a specialist, that she learned she had postpartum obsessive-compulsive disorder.

“It’s not a bad thing to be concerned for what’s going on with you or your child. The problem becomes when those concerns morph into something that becomes obsessive and detrimental to your lifestyle and being healthy,” she said. “These disorders during and after pregnancy affect people differently and show up differently at times in the same person, so it’s tricky.”

‘It’s OK to feel all the emotions’

Doll and Hess urge pregnant individuals to arm themselves with information and to lean on friends and family as well as medical and mental health professionals for support.

“Pregnancy and raising children are difficult without any additional mental health conditions,” Hess said. “It’s OK to feel all the emotions and to not feel embarrassed or scared to talk about them.”

Hess said the best way to keep up with the coalition’s events is to visit its website or on Facebook.

Inform Muncie articles are written by students in the School of Journalism and Strategic Communication in a classroom environment with a faculty adviser.

The Daily News welcomes thoughtful discussion on all of our stories, but please keep comments civil and on-topic. Read our full guidelines here.