Lindsey Ogle, assistant professor of special education, grew up living with her brother on the autism spectrum, Matt Ogle, whom she described as having very limited speech capabilities. Her family watched him struggle to find a job in rural Tennessee.

Even though her brother makes the most of his limited opportunities through volunteer work, he isn’t the only one who’s faced struggles finding employment. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the unemployment rate in 2022 was around twice as high for individuals with a disability compared to individuals without one.

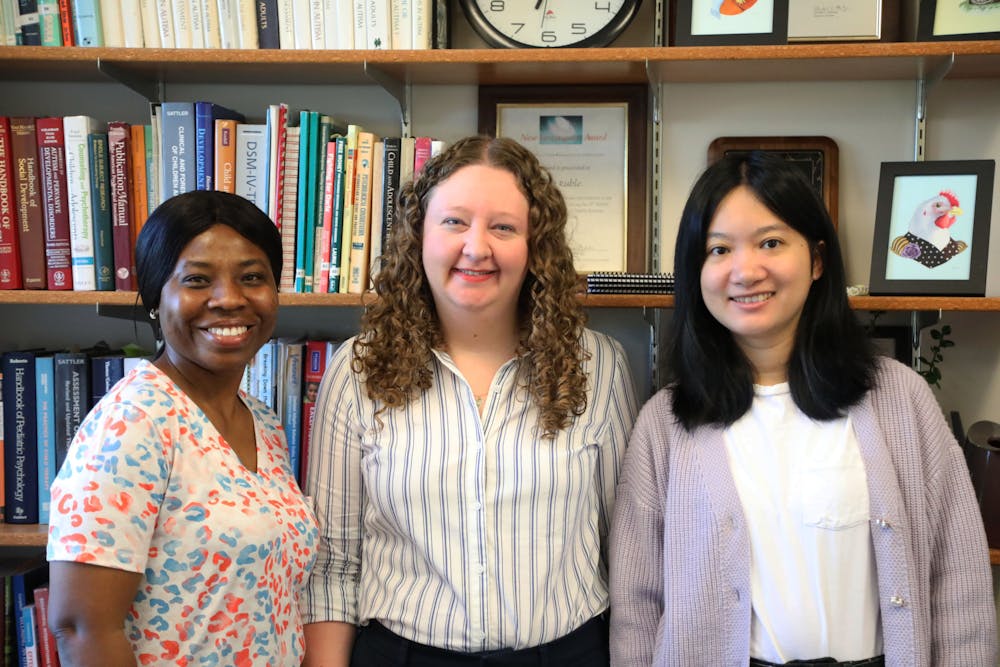

Now as a co-investigator for COMPASS (Collaborative Model for Competence and Success) Across Settings (CAST), an intervention project funded by the Institute of Educational Sciences (IES) through a $1,999,999 grant, Lindsey will help high school students with autism across Indiana find their place in society.

“We’re trying to improve their outcomes after high school because we know youth with autism have the worst post-secondary outcomes of any disability category,” she said.

CAST’s main goal is to help individuals with autism smoothly transition out of high school depending on their intended career path, whether through college or not, by working with parents and teachers to increase employment chances for each student. The program enables one of the first transition-planning intervention projects backed up by research to come to both the Department of Special Education and the Department of Educational Psychology.

This transition-planning project uses the COMPASS intervention method that begins with a consultation phase where goals are set for each student with plans to achieve them while maximizing the students’ strengths and improving their weaknesses.

“That’s where the youth with autism, if they are able to participate, they’re ideal to be involved in that process, and they absolutely should be able to talk about [employment goals],” Lindsey said.

In fact, Lindsey believes students with disabilities have just as difficult of a time figuring out their careers as their peers without a disability. To her, all adolescents experience self-discovery through a similar process.

“There are so many options and so much potential that it can be hard to choose, so I think every student needs guidance there and children and adolescents with autism are no different,” Lindsey said.

In her co-investigator role, Lindsey is giving to people with autism in a way she wishes the same was done for her brother. Her motivation as both a professor and researcher manifests through the influence he’s had in her life, which led her to help others with the same disability.

“If you can target those first few years after high school, then it sets an expectation and opens the door to more opportunity that my brother has not gotten in the same way I hope the students in our study will,” Lindsey said.

The study aims to make the transitional element of leaving high school, which Lindsey compares to falling off a cliff due to the lack of entitled services, much clearer for both the student and parent.

Primary investigator Lisa Ruble, professor and co-developer of COMPASS, mentioned the complexity of adult services causes the responsibility of advocating for post-secondary needs to fall on the parents and their children.

“What's different about the school system is that there’s federal law that guarantees services, but we don’t have that same law for adult services,” Ruble said. “We’re trying to get all that set up and help the families and the people with autism advocate for themselves.”

Along with parents and the school system, CAST also works with pre-employment specialists employed by vocational rehabilitation within schools to arrange students with autism with experiences providing jobs or college preparation.

“We’re integrating these three different groups that often just work in isolated ways so that we’re getting everybody on the same page,” Ruble said.

While finding opportunities such as jobs may be difficult, from her experiences working at Hillcroft Services’ ABA Clinic, chief ABA officer Gina Davenport noticed most individuals with autism in the clinic struggle with communication. Although she mainly works with children and some adolescents, Davenport believes communication is a crucial element to developing a person with autism’s ability to find a job and hold their own in adult life.

“If they’re gonna go out and advocate for themselves, they need to know how to have a reciprocal conversation,” Davenport said. “So we might teach them ‘If you say something, you have to wait for a response and acknowledge that person gave you a response.’”

Davenport said parents sometimes understandably do things for their child, whether having a disability or not, without ever teaching them how to do it. She believes parents teaching their child with autism skills while still at a young age helps them learn to do it themselves in the future.

“When you see somebody struggling, it’s human nature to want to jump in and do it for them, but, that’s a perfect teaching moment to teach them how to work through those struggles,” she said.

In terms of understanding autism, Davenport claims it’s difficult for people without a disability to relate if they haven’t been exposed to or interested in it. Even so, she believes educating individuals on the subject matter is crucial to empathizing with the struggles of people with autism.

“We're definitely getting better with more education now than when I started 18 years ago; however, it still needs a lot of work,” Davenport said.

Contact Zach Gonzalez with comments via email at zachary.gonzalez@bsu.edu or on Twitter @zachg25876998

The Daily News welcomes thoughtful discussion on all of our stories, but please keep comments civil and on-topic. Read our full guidelines here.