When Susan McDowell was 6 years old, her older brother taught her the periodic table.

McDowell collected rocks, and she read science books. She idolized Marie Curie, the first woman to win a Nobel prize. She converted her father’s work bench in their garage into a research bench, just like Curie’s.

Now Miami (Ohio) University’s vice president for research and innovation, McDowell has been in many different positions: as a biology student at Thomas More University in Crestview Hills, Kentucky, a technician at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Research Foundation, a postdoctoral fellow at Eli Lilly and Company, the assistant director of Ball State University’s biotechnology program and Ball State’s vice provost of research.

McDowell said she’s grateful for where she is now. When she joined Ball State’s biology department in 2003, she had the “unusual” experience of having a science department be equally distributed among faculty based on gender.

Though the biology department was equal, McDowell’s position as the vice provost at Ball State and her current position at Miami have been male dominated until the last five years, and that hasn’t been by chance, she said.

Predecessors, like Marilyn Buck who served as Ball State’s vice provost of academic affairs, “put a great deal” and “continue to put a great deal of effort and are very deliberate in trying to make sure that [they] are encouraging women to come into these leadership roles,” McDowell said.

When McDowell accepted the position as the vice provost, she said it “changed the trajectory of [her] professional career” and has enabled her to help more people than she previously could in her research labs and classes.

“I think the way I would characterize where I landed in history was I didn't have it as rough as some women before me, but I also would say that there were some struggles along the way,” McDowell said.

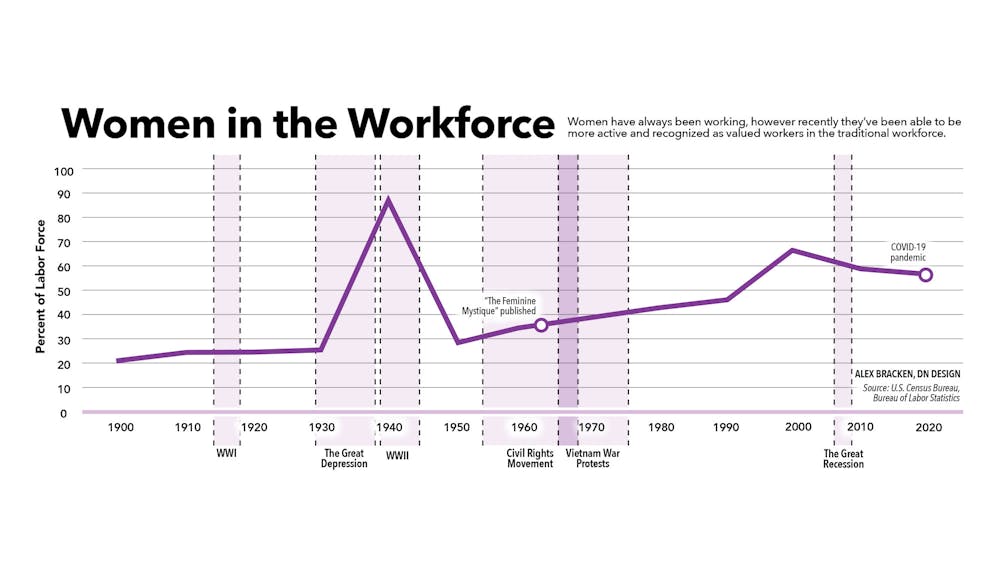

When it comes to the history of women in the workplace, Rachael Smith, assistant lecturer of women’s and gender studies, and Shiau-Yun Chen, assistant professor of history and women’s and gender studies, both highlight the fact women have always been working, but their work wasn’t recognized.

Though women were working prior to the Industrial Revolution, which started in approximately 1760 and ended around 1840, Smith said due to the new factories, there was a need for workers, which women filled.

During the revolution, women were paid less than men due to the justification that women would get married and pregnant and have to leave the workforce. Pregnant women in the workforce got fired because of this justification.

“There is this one-time justification that men needed to be paid more because they had wives and children to take care of, and therefore women got paid less,” Smith said. “Of course, we're also talking about a time where children were also in the workforce, and so children got paid less than women.”

After the Industrial Revolution, the next major boom of women in the workforce was during World War II, starting in 1939 and ending in 1945. After Pearl Harbor, many men felt it was their “patriotic duty” to serve, which opened factory jobs for women, Smith said. Women started to work in munition and in the military as nurses and pilots, and though they weren’t on the front lines, women were completing missions for the war effort.

“Now, again, women of color have always been working,” Smith said. “They were usually doing some type of domestic work, kitchen work, you know those types of things, but even now, now that those factory jobs came open, even women of color moved in to fill those vacancies as well.”

Smith noted that for women of color, especially Black women, entering the workforce during the war was the first time these women felt tied to their country, the first time they felt patriotic for their country.

According to the United States Census Bureau, starting in March 1940, the percentage of women employed 14 and older in all social classes was 86.7 percent of the population.

“They're everywhere that society will allow them to be,” Smith said.

A large part of why women were working was not only the need due to the war but also due to Rosie the Riveter.

“Rosie the Riveter, the woman, was chosen out of a group of women who were on the production line, and so she was basically one of them,” Smith said. “She actually was doing the job, but the whole idea was that it was propaganda to get women into the factories.”

Rosie’s message to women was, “We can do it!” She was telling women they can make their own money, they can be both mothers, wives and daughters and work at the same time, Smith said.

When the 1950s rolled around, white women and wealthy women of color were pushed back into the household, while poorer women went back to domestic work.

The 86.7 percent of women 14 and older in the labor force in 1940 dropped down to 29 percent in 1950, according to the U.S Census Bureau’s 1950 report.

“The damage was done because for years these women had access to their own money,” Smith said. “They didn't have to ask anybody for money. They didn't have to ask anybody to pay their way into this or that. They were earning their own money, and they were deciding how they spent it. That level of independence, the minute that you take that away, it's going to be problematic."

Feb. 19, 1963, Betty Friedan published “The Feminine Mystique,” which focuses on American housewives who were once working turning to alcohol and drugs “because they could not cope with their loses,” Smith said.

“The Feminine Mystique” brought about the second wave of feminism and lasted from the early ‘60s to the 1970s. Other factors in play during this second wave were the civil rights movement from 1954 to 1968, the Vietnam War protests from January 1965 to March 1973 and other countercultures of the time, Smith said.

During this wave, the Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed, which protects employees and job applicants from discrimination based on race, sex, religion, sexual harassment, pregnancy and national origin.

The Equal Pay Act of 1963 was also passed and protects people from sex-based wage discrimination and is based on performance of “substantially equal work in the same establishment.” This act bases pay off of experience, skill, effort and responsibility. The difference of pay is allowed based on seniority, merit, quantity or quality of work and other differing ways not based on sex.

The women involved in these movements were the daughters of the housewives in the “The Feminine Mystique.” They witnessed firsthand their mothers’ reactions to losing their independence, and these movements showed they could have it all and not be like their mothers, she said.

“‘I can have the marriage, I can have the children, I can have a career and I can use my brain, and it'll be good,’” Smith said. “As they started doing that, then that also became a problem and became an issue, and one of the big issues was that ‘You’re a bad mom because you're not at home with the children.’”

Smith and Chen said women get striked on pay due to maternity leave, and when it comes to promotions, men are picked over women. This goes back to the justification of women becoming pregnant, and they aren’t a permanent employee.

This is reason for the pay gap that shows up in women aged 25 to 40, which Chen said is the average marriage and pregnancy age.

Chen said this model of the work environment hasn’t been updated. Because it follows a masculine model, women sometimes have to fit into “the norm.” Women will sometimes sacrifice elements of their feminity to assimilate into the male-dominated workforce.

Being authentic to herself is important to McDowell, but she also found on occasion she would need to sacrifice femininity, and she would advise students, particularly females, to pay attention to their voice inflection. She said an “up inflection,” a more feminine trait, could undermine how one is coming across.

“I think I probably am cognizant of some ways that I think it's important to come across in order to meet some common ground, but as long as I'm being authentic, I've been able to reconcile that,” McDowell said. “So, I wouldn't say that I sacrifice or disregard my femininity, but I also would say I'm very deliberate in how I present myself.”

Kristen Ott, a process development engineer at Boston Scientific– Spencer, Indiana plant, like McDowell believes being authentic to oneself is important. Though she has never felt the need to sacrifice her femininity, comments have been made about how she dresses, but she’s had management come to her aide.

Ott studied bioengineering at the University of Toledo, where she said the gender divide was more visuable than in the field. She said in mechanical and electrical engineering, the “old fashioned type of engineering,” was where the divide was seen most.

Brooke Bonek, third-year computer technology major, and Allysa Britting, third-year architecture major, are both current students in male-dominated fields.

Bonek, as a computer technology major, is used to being one of two to three women in a classroom, and she’s used to those numbers dwindling in her classroom after others dropout.

“I think it's so few because since it is male dominated, they think they can't really stick through it,” she said.

In her three years at Ball State, Bonek hasn’t had a female teacher for her major, and there are four women faculty members in the computer science department.

“It honestly makes me empowered,” Bonek said. “I think that me just being in that class can show that these guys aren't the only ones that can pursue this career type, and I feel like … I can show them that I can do just exactly what they do.”

Britting, on the other hand, feels more equal in the classroom but not in the workforce. According to the 2022 U.S Bureau of Labor Statistics, only 29.8 percent of architects, excluding landscape and naval, are women.

The classroom isn’t the only space Bonek and Britting have operated in. Bonek is a production lead for Ball State University’s Varsity Esports team, and Britting was a member of her high school’s robotics club.

For Bonek, she is on a production team of five with four women, the most women to be on the production team, but in years previous, she’s been one of two or three. The players she produces over have been predominantly men, with one or two women sprinkled through.

Bonek has been with the team since her second year.

Britting was one of seven girls on a team of 50 for her robotics team in high school. In high school, she took an architecture and civil engineering class where she was the only woman in a class of 15.

“It's never super bothered me to be with more men in my field, but I also do know that they don't always understand my experience and my perspective being a woman,” Britting said. “It just makes it hard too. I feel like sometimes I have to work twice as hard just to get my point across, because sometimes I feel I won't get taken as seriously because people look at me like I'm different and I'm an outcast in that area.”

The advice McDowell, Bonek, Ott and Britting have for women reflects the history of what women did before in the workplace.

“I think the world is changing and trying to get better at it, but also [women need] to just not be afraid of it, to [not] be afraid of that challenge because I think there are a lot of good things that I've gotten from those experiences,” Britting said.

McDowell advises women in these fields to find strong, successful female mentors and to be “picky” with them.

Ott advises women to be confident, to not hide their femininity, for them to positively contribute to changing the culture and to speak up.

“I would tell them just to make sure you stick up for yourself and that you don't try and hide yourself away from the guys that obviously try and see if they can overpower you,” Bonek said. “I would say always stick through it and make sure you're pulling yourself up.”

Contact Hannah Amos with comments at hannah.amos@bsu.edu or on Twitter @Hannah_Amos_394.

The Daily News welcomes thoughtful discussion on all of our stories, but please keep comments civil and on-topic. Read our full guidelines here.