Editor's Note: This story has been updated.

Most emergency room visits in March 2020 in Chicago were some of the city’s earliest COVID-19 cases. By the end of the month, the official website for the city of Chicago shared a report stating nearly 3,000 positive COVID-19 cases were identified within city limits alone. While most patients reported symptoms including a dry cough and shortness of breath, Braxton Williams checked into the ER feeling weak and nauseous.

What he thought was food poisoning, Williams said, ending up being his kidneys functioning at 7% of their capacity. He was dying, and doctor’s didn’t know why.

“There was some conspiracy that some people were getting kidney failure after having COVID,” Williams, 2020 Ball State sociology graduate and poet, said. “I hadn’t had COVID. I hadn’t even been tested.”

Williams and his mother, Lenetta, racked their brains for what could possibly be causing Braxton’s kidneys to give up on him. Lenetta found an article saying another Muncie local was diagnosed with kidney failure after drinking directly from the city’s tap water, Braxton said, but doctors didn’t think Muncie’s water was the issue, and neither did Braxton or Lenetta.

“I have no clue what happened,” Braxton said, “but I was really sick. I was in the hospital for a week alone, and that experience really shifted my mindset. I want to do everything I can before I actually pass away.”

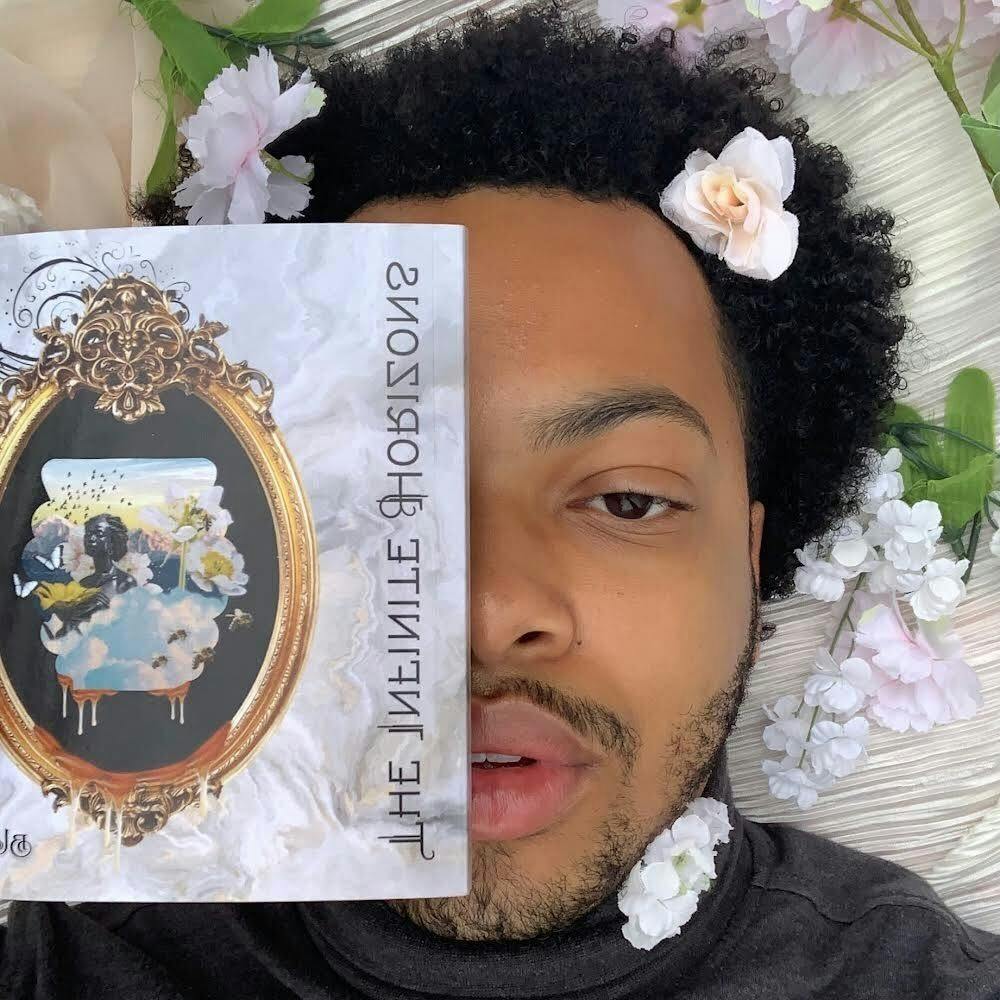

Braxton found himself turning to an outlet he discovered while at Ball State: creative writing, and, within six months, he self-published his first book. While in the hospital, Braxton wrote a poem called “Room 6105” about his experience in the hospital, which is now part of his 124-paged book, “The Infinite Horizons.”

His journey to find his infinite horizons, Braxton said, wasn’t easy. But, through the creative recollections of his personal experiences, Braxton hopes to help others find their infinite horizons, too.

Books Before Blacktop

Every afternoon, when the bell rang for lunchtime and his classmates’ stomachs grumbled at the thought of the chips in their lunchboxes, Braxton swung his backpack over his shoulder and made his way to his reading class.

Throughout grade school and until Braxton was a freshman in high school, he struggled with his reading and writing skills. His teachers took extra time with him to get him up to speed, working on his comprehension and reading capability while other students played kickball during recess. Braxton found it difficult to feel confident in what he wrote.

“Everyone writes little notes and stuff in their notebook, but mine was never artsy or metaphoric or anything like that,” Braxton said.

In fact, Lenetta said she remembers when Braxton was 3 years old, and she “forced” him to lead the psalm at her church.

“It was so funny because he just did not want to do it,” Lenetta said. “Long story short, we had a beautiful church, and he led the psalm, but I crack up because, in retrospect, I was thinking, ‘The arts just aren’t his thing.’”

Braxton’s active annoyance and frustration led Lenetta — and the rest of his family — to believe the arts weren’t his calling, and he said he was never confident in his writing skills until his senior year of high school when he took a creative writing course with one of the school’s English teachers, Miss Mustafah.

“That's when I started actually writing creatively and artistically,” Braxton said.

Start of Something New

When it came time for college, Braxton moved from the south suburbs of Chicago to Muncie to attend Ball State as it made the most sense opportunistically and financially. When he began his college career as a nursing major in 2017, his focus shifted more toward studying for the Clinical Performance Assessment Tool (CPAT) than expressing himself through stanzas. But, after two and a half years of anatomy lessons and learning how to insert catheters, Braxton discovered his passion laid elsewhere.

“I took the CPAT, and I didn’t pass,” Braxton said, “but I wasn’t sad about it. I took that as a sign that I probably wasn’t passionate about nursing to begin with.”

After talking to a friend about his interests, Braxton decided to switch his major to sociology. Lenetta said, because Braxton has always been an active listener and engaged in conversations, the change made more sense to her than nursing.

“He was so engaged in it, and it was a wonderful thing,” Lenetta said. “It just helped to open up other areas in his own mind and his writing and his inner feelings.”

Braxton immersed himself in classes on race and ethnicity, gender and sexuality and women’s history, learning topics he said made him feel both invigorated and mentally exhausted, and from there, his understanding of the world began to develop. While the realizations helped inspire him to pick up his pencil and write again, the more knowledge Braxton gained about the world, the more he struggled to accept how negative it could be.

“With sociology, not only do you learn a lot about the world, but in that comes a mirror of learning about yourself as well, which I never really thought about in great depth until I started going to these classes,” Braxton said. “They really opened me up to a world outside of myself. They opened my heart to accepting myself and accepting others.”

A Formal Introduction

After switching his major, Braxton realized he had more room in his schedule for electives, so he decided to take a creative writing class with Michael Begnal, assistant teaching professor of English. One course opened the door to dozens more, Braxton said, so he decided to take poetry writing with Peter Davis, assistant teaching professor of English.

“He was terrific,” Davis said. “He was obviously a very nice guy, came to class, but he was also willing to share his thoughts and participate. I knew, even before class was over, that he had something more to say — the motivation and the desire to [say more].”

Braxton’s desire to say more, Davis said, was evident through the work he submitted for class assignments. Whereas there is an abundance of negativity in artwork, Davis said Braxton “made a work of art, put it out into the world and made it a positive thing to be doing so.”

“One thing about his writing is it’s not necessarily unique, per se, but Braxton’s poems are positive in a way that they are encouraging,” Davis said. “A lot of people write poems when they are depressed. Braxton was not like that, and I really appreciated the positivity in what he was doing. He was consciously trying to add something beautiful to the world.”

After 16 weeks of writing different types of poems, Davis instructed his class to compile a series of 10 to 15 of their favorites into a chapbook as their final project, something Davis typically makes his students do at the end of every semester to encourage sharing one another’s work. Each student had to bring at least five to swap with others in the class.

“I took myself to the printing lab in the library, printed out a bunch of copies and hand-stitched the seam in the middle to bind it together,” Braxton said.

Once his chapbook was complete, Braxton shared it with his family as well as his classmates, and Lenetta said his writing “blew [her] mind.”

“I was so emotional. I just kind of cried,” Lenetta said. “Just to get inside my baby's head, you know, just to hear him and his voice. It just really blows my mind when I even revisit his book.”

Braxton decided to sell more copies of his chapbook off of his Instagram for $5 — then $10 — until he ran out of money for printing in Bracken Library. He stopped printing and selling his chapbook once he ran out of funds, Braxton said, but sharing his writing stemmed from Davis’ final chapbook project.

“I think, overall, that was my starting point,” Braxton said. “It was a way for me to see the manifestation [of my book] come to light. I wanted to publish a book, and people wanted to read it.”

Outlook and Opportunity

After seeing how much friends and family enjoyed his chapbook, Braxton said, he reached out to Begnal, who told him the best place to start in getting published would be submitting poems to literary magazines and online publishing companies.

After a number of denials, lack of feedback and complete silence, Braxton said, “since nobody is giving me the opportunity, I’m going to give myself the opportunity.”

He began researching the process of self-publishing and discovered Amazon’s Kindle Direct Publishing (KDP) program, which allows users to self-publish e-books and paperbacks for free. He took advantage of the opportunity to write on his own time, publish at his own pace and pay as little as possible to turn his book into a reality.

Braxton hit the peak of his work in summer 2020, right around the time of his unexpected emergency room visit, which put a pause in his progress. His kidneys functioning at 7% required a month of dialysis in the hospital and a catheter in his chest.

“That experience shifted everything,” Braxton said. “I wanted to self-publish, for real. I wanted my book to represent, per se, my last words, my goodbyes. I wanted to put everything into the book that I could, everything that I have felt or experienced, and build forever off of that.”

After one more month of dialysis back home, Braxton was healthy enough to begin writing again, and on Sept. 18, 2020, he self-published "The Infinite Horizons" on Amazon. In 124 pages, Braxton aims to capture the importance of the “natural swaying of the good and bad” in one paperback book packed with poems, photographs and pages to write and reflect on his words.

Where Worlds Align

Braxton said he defines the infinite horizons as the balance many strive to achieve in their lives, the beauty in our favorite city’s skyline and how the clouds dance with the sea. Infinite horizons exist in the emotions we mask, the tears we do not shed and the smiles we do not show. Through analysis and understanding of these infinite horizons, Braxton said, it is possible to develop a better understanding of life and who we are meant to become.

“If you can find a horizon to stare into, what lies ahead is the infinite horizons — multiple worlds align,” he said. “It’s something that takes your breath away, a place where you can see everything.”

When Braxton began writing “The Infinite Horizons,” he said he set out with a goal to “create a feeling” in the infinite horizons, one that explores what life is really like.

“It feels scary at times watching the horizon. It feels vulnerable, but it's so beautiful, and it's so diverse and mesmerizing,” he said.

When he recalls reading the poems Braxton submitted for class, Davis said one thing that always stood out was the feelings Braxton compelled through his words, and Lenetta said Braxton has been “an atmospheric change from the moment he was born” — in her life and the lives of those he meets. While she hopes he “writes 50 more books” to continue changing others, “if that’s not in his heart, that’s fine, too.”

“He has so much to give to people,” Lenetta said, “and [his books] may not ever reach the top selling list, but I'm a firm believer that whomever [his book] encounters, it is going to change their lives.”

In his letter to his readers in his book, Braxton said he doesn’t believe the time is ever right — there is no knowing when to search for your infinite horizons — but he believes there is a right time to read the right words. There is a moment, he said, where what you read will resonate with you on a level strong enough to make an impact on the decisions you make, and that’s the day your journey to find your infinite horizons will begin.

“Trust the journey,” Braxton said. “Sometimes, you have to carve your own opportunities. Life, especially at our age, is constantly filled with something new. You really only have one life. I want to do as much as possible and create and express as much as I can, and hopefully help other people along the way.”

Lenetta said she knows Braxton sets high expectations for himself, so she finds it important to remind him to take things one day at a time and to remember change doesn’t happen overnight.

“Put it in writing. Let people hear your story, and I promise whoever it was intended to reach, it will reach,” Lenetta said. “It’s going to change lives, but we do it one at a time. We can't change the world all at once, but if we reach a person one at a time, that's all that matters.”

The main way he sets out to help others, Braxton said, is through writing relatable words. While we all live different lives, in the end, Braxton said, we are all the same. Though we may be divided by social constructs, we share the emotions we experience.

“In the end, I want people to say, ‘I can relate to this poem,’” Braxton said, “which, in relation, means you relate to me. You will eventually find a piece of me in you.”

Contact Taylor Smith with comments at tnsmith6@bsu.edu or on Twitter @taywrites.

The Daily News welcomes thoughtful discussion on all of our stories, but please keep comments civil and on-topic. Read our full guidelines here.