Content Warning: This story contains detailed descriptions and images related to health and weight loss that may be triggering to some readers. Please read with caution.

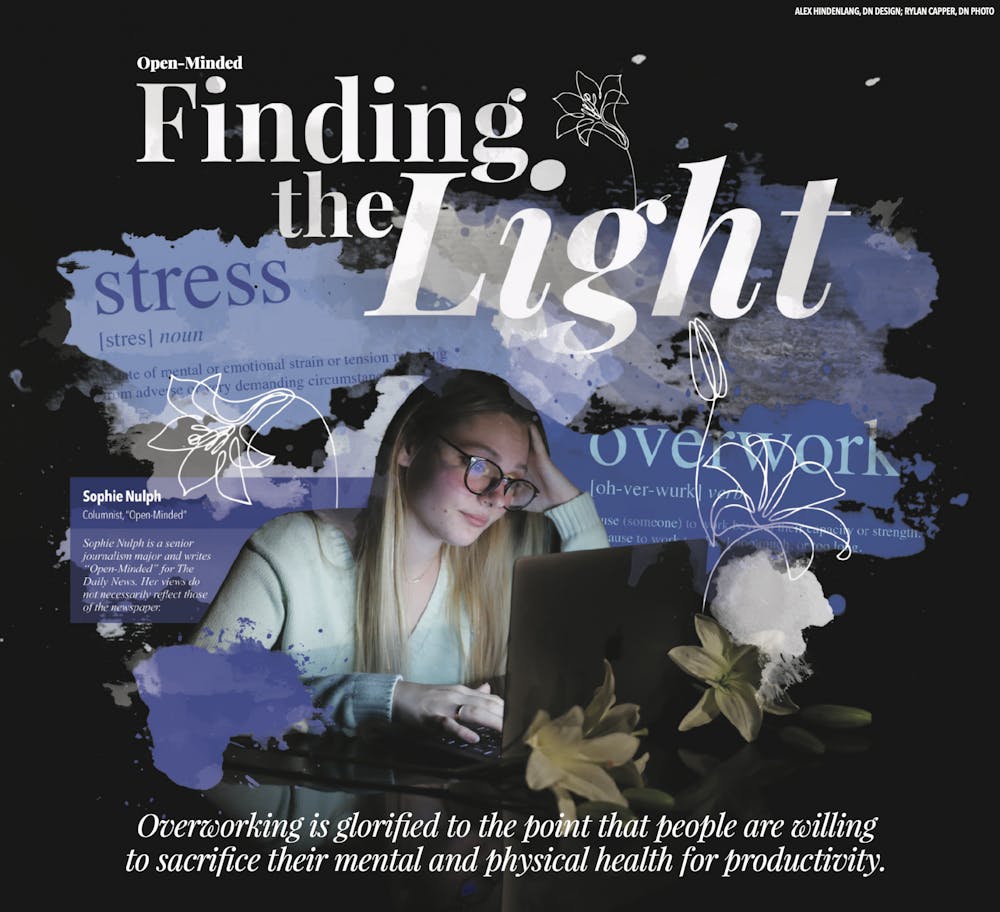

Sophie Nulph is a senior journalism major and writes “Open-Minded” for The Daily News. Her views do not necessarily reflect those of the newspaper.

A year ago, my body broke.

It started with a hangover. I was embarrassed, so I didn’t tell anyone about the intense sickness I felt in my stomach. After a week, it hadn’t gone away. Soon after, I found myself aching from vomiting multiple times a day, and my doctors chalked it up to a thyroid medication I was taking.

Months later, I laid in my bed silently letting the tears stream down my face. I was too weak to shower, too weak to eat, too weak to even use the bathroom by myself. A darkness had set over my life, and I fought to find the light to grow.

I had no idea what was happening to me, and the doctor’s best guess was as good as mine. Over the course of six months, I lost everything. My weight was dropping as rapidly as my grades because I couldn’t attend classes, and I had to quit everything I loved. I struggled through the spring, keeping my head down and hoping my professors would be forgiving with the ever-looming doctor’s note above my head.

Officially, I had a stomach ulcer, but after five more months of medications and follow-up visits, I still said “hello” to the toilet bowl before I could greet the sun in the morning. While my physical health continued to decline, my mental health rapidly spiraled with it, perched on a cliff like I had Bonnie and Clyde sitting on each shoulder, double-dog daring me to turn the car off the edge.

Turning down opportunities turned into necessity, and survival became the top priority. Throughout college, I was told I needed to do as much as I could outside of classes to build a successful career. Each year of college, I added a new responsibility to my plate, and soon my plate became a full three-course meal.

As a junior, in September 2020, I held an editor position with The Daily News, worked in an unpaid internship with the Center for Peace and Conflict Studies, took 16 credit hours, held a part-time job through the campus technology center, freelanced articles to local papers and took the next step in my five-year long relationship by getting a Great Pyrenees puppy.

I had no idea what I was getting into.

On top of all of this, I was living on my own for the very first time. While dormitories intend on making the transition from childhood to adulting easier, nothing prepares you for the amount of cooking, cleaning and bills — they really do come every month — that are required to stay alive and afloat.

When my body broke, my mind couldn’t hold on by itself.

Overworking, or burnout, doesn’t have to look like having the flu or a hospital visit. It can be as simple as holding your urine until your bladder feels hard to the touch or skipping lunch because you’re too afraid to miss a deadline. Ignoring the needs of our bodies to the point of neglect is praised as hard work even though the effects are detrimental — women who hold their urine have a higher chance to develop a urinary tract infection, and 28.8 million people already suffer from disordered eating in the United States, the second-deadliest mental illness.

Glorifying the idea of overworking is furthering these initiatives that our economic output is more important than our personal input.

A year later, I still spend the early morning hours on the bathroom floor, willing my body to keep my stomach acid down. I am 65 pounds down, and most of my diet to this day consists of goldfish crackers, if anything at all. The darkness surrounding me still loomed overhead like storm clouds waiting to wreak havoc. I am on two types of anti-anxiety medications, an antidepressant and a stomach acid-reducer in order to get through my day. Overworking can affect more than your mental health, and my body is a living testament to that; I am still recovering, sleeping more than normal and requiring more help than I’d feel comfortable asking for.

Overworking to the point of mental strain is not a new concept in the modern workforce. Job burnout has become such a popular illness — preventative measures can be found in scientific journals and basic secondary sources, such as MayoClinic. The term was originally used colloquially, taken from the drug world and redefined from the long-term effects of drug use to gradual emotional depletion and lack of motivation. According to a study posted by the American Psychological Association (APA), burnout first emerged in the 1960s, mostly in industries that involve civil work and has continued to grow in research and prominence.

The APA shows society displaying burnout in exceedingly early circumstances, leaking into universities and high schools like an odorless gas, helplessly taking over the minds of anxious, overworked teens. The pressure for teenagers to surpass others academically is more overbearing than ever in the race to see how many college credits you can take with you from high school. According to TransferIN, 79 Indiana high schools offer some type of dual-credit courses with eight different programs to choose from. At my high school, they offered Advanced Placement (AP) courses for college credits as early as freshman year.

The pressures only worsen the older we get. Jobs require more education, certification and experience than ever before, and according to educationdata.org, the average student leaves their university with more than $30,000 in debt. Overworking in college can sneak up on you, disguising itself as four hours of sleep or partying every night to distract from the intrusive thoughts.

Burnout is seemingly inevitable in current work environments, yet preventative measures are not taught in school and are ignored as the pressures of job insecurity leave little room to recover properly from overworking. The COVID-19 pandemic has amplified the importance of mental health days while simultaneously robbing people of their safe spaces to relax and recover. Suddenly, our beds and kitchen counters have turned into our lecture halls and conference rooms.

I wake up every day wondering who I have become because I feel like my identity was stripped with my extracurriculars. My safe space has been stripped and mashed with the impending feelings of deadlines — even on weekends. I am slowly learning who I am, what I love to do, and slowly accepting that I don’t have to follow the degree I have been working to earn for the last four years. I am slowly learning to separate time and have deliberate spaces.

I have begun searching for the benefits of darkness, rather than fighting to find the light. I am not only growing in the new darkness, I'm beginning to bud.

For the first time since middle school, I have a desk I use as more than just a storage area — littered with old cereal bowls two months too late to wash and half-emptied water bottles collecting dust. I also force myself into the library for homework at least twice a week and try to designate specific hours to myself for gratitude and self-care, something I’ve never known how to prioritize.

The consequences of overworking need to be normalized, not glamorized. Burnout, prevention and recovery measures should be taught in high schools and basic university courses, and we should teach what normal boundaries look like. In virtual schooling, designating breaks geared toward stretching students’ minds and eyes should be enforced to help with blue-light headaches and short-term burnout.

While prevention can be taught, most people don't realize they are overworking themselves until it's too late to take preventative measures. Teaching what burnout looks like in school and the workplace is essential to prevent overworking for future generations. Don’t stop going out for extracurriculars, but don’t feel pressured to take on everything to build your resume. People can find their passions while evaluating their hobbies and dropping extracurriculars that no longer serve them.

I am nothing without my degree path, or so I thought six months ago. My battle with my body feels like a never-ending war in my mind, but a treaty is finally starting to be negotiated. Overworking is not a completely breakable habit because society’s standards continue to grow and change. However, there are ways we can learn to put ourselves above our work and ways to avoid burnout from happening too frequently. I am slowly learning to love my body and my mind for what it is, and I am accepting that I don’t need to fill my schedule down to the hour with my rainbow pens to feel accomplished anymore — and I’m proud of that. Like peace lilies thriving in the black, I am blooming, and my darkness has found a new love in its growth.

Contact Sophie with comments at smnulph@bsu.edu and on Twitter @nulphsophie.

The Daily News welcomes thoughtful discussion on all of our stories, but please keep comments civil and on-topic. Read our full guidelines here.