The word that comes to mind when Karen Vincent, board president of the Delaware County Historical Society, thinks of feminism is “recognition.” She said she wants to recognize the women involved in the decades-long U.S. suffrage movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries through the Historical Society’s current exhibit, “The Suffragists of Delaware County.”

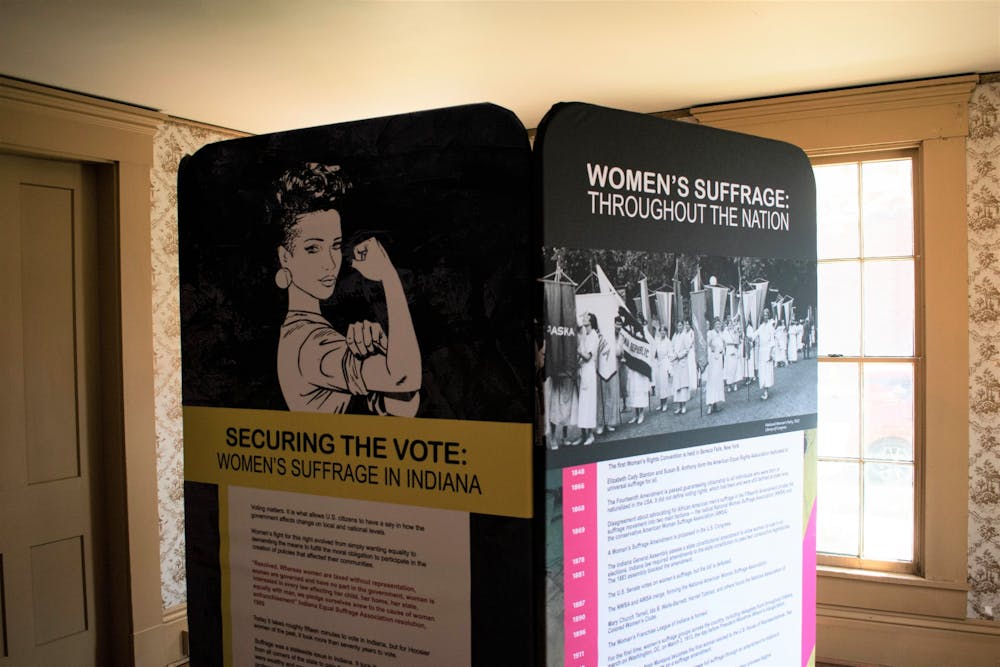

The exhibit is held in the Moore-Youse Home Museum in downtown Muncie through Sept. 29, along with an exhibit from the Indiana Historical Society titled “Securing the Vote: Women’s Suffrage in Indiana.” It honors several local women from Delaware County who made an impact on the suffrage movement at large.

“We narrowed [the suffrage movement] down and picked out about ten local women out of hundreds and hundreds … who were very involved in the suffrage movement here,” Vincent said. “So, everything from Susan Ryan Marsh … to a couple of African American women who were very involved.”

The exhibit was originally slated for September 2020, but pushed back due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Planning began with a group Vincent formed in 2018 with Melissa Gentry, maps collection supervisor at Bracken Library, called Notable Women of Delaware County.

“This came out of just several of us chatting together and trying to figure out if we could come up with 100 women who made a difference in Delaware County,” Vincent said. “We have a list of about 400 now.”

This number indicates wide support for the women’s suffrage movement in Delaware County, Vincent said, with the Muncie branch of the Woman’s Franchise League of Indiana at one point having more than 250 members between its formation in 1912 and its last meeting in 1920.

“I’ve never seen an exact number, but you had hundreds of women,” Vincent said. “It wasn’t single digits or even double digits.”

Among these women were Elizabeth Brady Ball, Bertha Crosley Ball, Emma Wood Ball, Frances Woodworth Ball and Sarah Rogers Ball, the wives of the Ball brothers. Lucius L. Ball was also a member of the Woman’s Franchise League.

However, Vincent said women with influential husbands weren’t the only ones involved in the movement.

“There were a lot of teachers involved,” Vincent said. “There were the working women — one of the people we feature over there is Reba Hoover, who worked [at the Eli Hoover Company].”

A group of posters from the Smithsonian looks at the women's suffrage movement from a national perspective. It complements a local exhibit from the Delaware County Historical Society and a state exhibit from the Indiana Historical Society that provide visitors with a broad outline if the movement. Joey Sills, DN

One prominent local suffragist was Ida Husted Harper, who gained national recognition with her three-volume biography of Susan B. Anthony. Born in Franklin County, Indiana in 1851, Harper moved to Muncie when she was ten years old and graduated from Muncie High School in 1868. She began her career as a journalist three years later in Terre Haute, Indiana. She met Anthony through journalism, and the two began a friendship that culminated with their collaboration on “History of Woman Suffrage,” a six-volume collection which also featured the work of suffragists Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Matilda Joslyn Gage.

Although Vincent said Harper would become the only suffragist from Delaware County to gain national recognition, the Historical Society’s exhibit does not focus on her specifically. Vincent said she hopes visitors leave with a better appreciation for women who weren’t as well-known and who made a difference at the local level.

“Talking about the early women’s rights movement and talking about our notable women of Delaware County just brings up a more well-rounded view of history, a more well-rounded view of this area,” Vincent said. “History isn’t made by one person or one group of people.”

This philosophy of well-rounded history is on clear display, as the exhibit gives equal representation to the influential Black voices of the suffrage movement. Vincent said Black women in Muncie and other surrounding cities were declined membership in the Woman’s Franchise League, inspiring many to create their own organization called the Booker T. Washington Franchise League in May 1917.

Even after the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920, Black women specifically had a harder time exercising the right to vote.

“I think most Black women had an approach from the beginning, and even after the 19th Amendment of, ‘OK, we’ll work toward this amendment, but we also really need to work towards … making it meaningful,’” said Emily Johnson, Ball State assistant professor of history.

The exhibit notes that racial discrimination in voting wasn’t prohibited until former President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law in 1965.

Native American women were another influential group during the fight for suffrage, Emily Johnson said, with their native nations often allowing them the right to be directly involved in the political process.

“There were actually … people in the mainstream suffrage movement who used the example of Iroquois women in particular to say … ‘Here is a society where women have had the right to vote, [who] have had equal citizenship — let’s use that as a model,’” Johnson said.

Like Black women, Native American women continued fighting for political franchise beyond 1920, not gaining suffrage until the passing of the Snyder Act in 1924, which granted Native Americans born in the U.S. full citizenship.

However, even with the right to vote no longer denied on the basis of race or sex, the feminist movement today still fights for recognition of broader equal rights.

The "The Suffragists of Delaware County" exhibit stresses the fight for equal rights isn't over. The Delaware County Historical Society is hosting two exhibits through Sept. 29 focusing on local figures influential to the U.S. women's suffrage movement. Joey Sills, DN

According to the exhibit, “Today, women are still fighting for economic equality, freedom from sexual harassment and domestic violence, reproductive rights, racial justice and LGBTQ rights.”

Regardless of these ongoing battles, to women like Kourtney McCauliff and her mother, Kathy McCauliff, both members of the Historical Society and volunteers for the League of Women Voters, the suffragists' fight still means something today, even if it feels their work has yet to be completed.

“Although they got kind of the first step of women’s rights, we’re still … working on steps three, four and five,” said Kourtney McCauliff, “But it’s good to remember … where we started and help us remember where we are going.”

Kathy McCauliff said her mother was born in 1920, the year the 19th Amendment was ratified.

“My mom often talked about — when she was old enough to vote — being able to vote,” Kathy McCauliff said. “So, voting became critical to my childhood and now to me as an adult, which I then tried to pass on to my children.”

For both Kathy and Kourtney McCauliff, the word that comes to mind when they think of feminism is “equality.”

“I would say equality comes to mind right off the bat,” Kourtney McCauliff said. “And then … also just a movement that keeps on moving.”

When reflecting on the current state of the feminist movement, Vincent said she believes there are many lessons fourth-wave feminists today can learn from their first-wave counterparts.

“Frankly, the doggedness of those early women who started in … the mid-1800s and earlier,” Vincent said. “And the absolute stubbornness of never giving up on that — I mean, there’s always lessons to be learned from that.”

Johnson said she believes many feminists today have done work to make their movement more inclusive by developing a focus on intersectionality.

“I think a lot of feminists today are really aware of the ways in which earlier feminist movements … failed to adequately include minoritized women,” Johnson said. “I think there’s also a much greater focus on LGBTQ issues.”

For Johnson, no single word comes to mind when she thinks of feminism.

“I guess what comes to mind first for me is … the idea of a big tent — there are so many different … priorities and kinds of feminism and kinds of issues and ways of approaching feminism,” Johnson said. “It’s a really big term that encompasses a lot of different things.”

Contact Joey Sills with comments at joey.sills@bsu.edu or on Twitter @sillsjoey.

The Daily News welcomes thoughtful discussion on all of our stories, but please keep comments civil and on-topic. Read our full guidelines here.