When Stacy Steggs was about 8 years old, her grandmother was her first student she taught sign language to.

Steggs was born Deaf, and she had signed exact English until she was 12 years old and attended the Nebraska School for the Deaf. There, she was exposed to American Sign Language (ASL) for the first time, and she said she was forever changed as she fell in love with the language.

She later attended Gallaudet University — a private university in Washington, D.C. for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing since 1864 — where everyone used ASL across campus from the classroom to the cafeteria. While she initially wanted to pursue a career in counseling, she later became an ASL instructor.

In her two decades-long teaching career, Steggs has taught at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis and other community colleges and universities in Washington. Now, Steggs teaches ASL classes at Ball State as a part of the university’s teaching major in Deaf/Hard of Hearing — the only undergraduate program of its kind in Indiana where students take classes in ASL, Deaf education and teaching methods for K-12 students who are Deaf or Hard of Hearing.

How do certain facial features express grammar in ASL?

- Your eyebrows can indicate the grammar of ASL. If someone is signing and their eyebrows are raised, this indicates a question.

- Your mouth can indicate adjectives in ASL. While someone is signing and moving their mouth, how big their mouth is open can indicate how small or large an object they’re signing is.

Ball State’s ASL classes are all taught by Deaf faculty members like Steggs because it isn’t culturally appropriate for hearing people to teach sign language. In Steggs’ beginning ASL classes, students learn how to have casual, everyday conversations in ASL relating to family, clothing and food. Students are also introduced to how facial expressions play an important role in ASL.

“ASL has real grammar, and you have to use your whole face for it,” Steggs said via an interpreter. “Same as a hearing person — if they were to speak, they would have tone in their voice. We have tone in our face. It’s a major component of ASL, and people are floored when they learn that. ASL structure has to be learned, syntax has to be learned — all sorts of things people are unaware of. We have our own culture. People have no idea about that outside of this discipline.”

In Steggs’ classroom, she uses ASL cultured sitting, where students’ desks are arranged in a semicircle, so everyone can see one another to communicate. Steggs doesn’t have a lot of written English in her classroom; instead, she uses a PowerPoint with visuals and videos because ASL is a visual language.

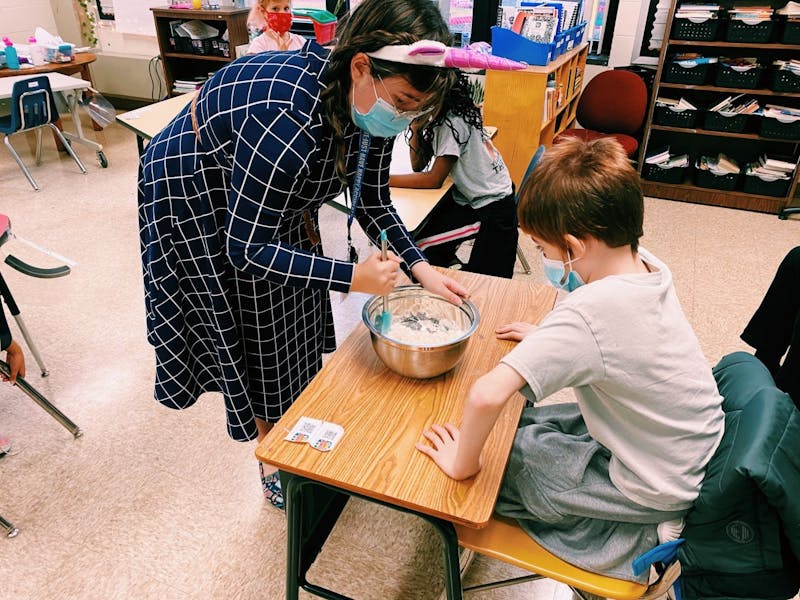

She also pairs her students together for hands-on activities, so they can interact with one another to practice signing. Whenever students are in her class, Steggs has them turn their voices off because in Deaf culture, people don’t talk as they sign.

“It's required in order to pick up this language, you really have to be immersed in it,” Steggs said via an interpreter. “This is not something you can gain from reading a book. You have to continuously learn the language and live it in your life. It's a lifelong journey. Same with English — I grew up with English, and I'm still learning English even as an adult. It's my second language, and I will be a student myself for life.”

In addition to learning ASL in Ball State’s Deaf/Hard of Hearing program, students also have coursework in Deaf education. Raschelle Neild, an associate professor of Deaf education, said her classes prepare students for their future as teachers who know how to accommodate and modify their teaching methods to meet their Deaf and Hard of Hearing students’ unique needs. This includes knowing how to write individualized education plans and use assistive technology with their students.

“With society or technology, as new words are added to our vocabulary, there are also new words added to ASL,” Neild said. “Deaf people in different regions and different personalities sign differently — the same [way] people use English. This takes getting used to — it isn’t seeing the sign in the book, and then that is what it will look like when a person really signs it to you.”

Indiana School for the Deaf

To learn ASL and about Deaf culture in a fully immersed environment, sophomores within Ball State’s Deaf/Hard of Hearing program have the option of completing a year-long residential practicum at the Indiana School for the Deaf in Indianapolis.

Kaitie Gucinski, a 2019 Ball State alumna, said living in the dorms at the Indiana School for the Deaf and waking up every day fully immersed Deaf culture was truly the best experience. As she worked alongside teachers at the school, Gucinski had first-hand experiences learning teaching strategies for Deaf students that she wouldn’t be able to learn in a college classroom or from a textbook.

“Ball State only offers up until ASL 4, and that is not nearly enough vocabulary or practice that you need to be able to effectively teach Deaf children,” Gucinski said. “The school gave me practice with communicating with people with various abilities and various language needs. It really helped strengthen my own language so that I could better serve students.”

Sarah Norris, a 2017 Ball State alumna, said working with kids is where her heart is at. As she ate lunch with middle school students during her practicum, she learned a large amount of vocabulary that’s not used in a classroom setting, such as social language and holiday signs.

During her practicum, one hurdle Gucinski experienced was just learning to communicate in her second language because it was the first time her primary mode of communication wasn’t her first language, and it was frustrating when her brain wasn’t quite making the switch from English to American Sign Language.

Gucinski also remembers her eyes being constantly tired because she wasn’t used to having to visually retain so much information.

“I really had to get my brain used to visually processing a lot more than you normally would,” Gucinski said. “As a hearing person, I can sit in a meeting and I can sit and write or drift off, but I'm still able to hear what's going on around me versus you have to be a super active participant to be able to get all the things visually.”

Amy Hackett, a 1989 Ball State alumna, said she had never met a Deaf person until her practicum at the Indiana School for the Deaf.

“I remember the very first night I was there, a little preschool student came up to me and asked me for candy, and I didn't even know the sign for candy,” Hackett said. “It was a really quick sink or swim kind of experience where you had to pick up as much as you can as fast as you could.”

Now, Gucinski, Norris and Hackett are all elementary teachers at the Indiana School for the Deaf.

With eight students in her third grade classroom, Gucinski adapts her curriculum to make sure everything is visual. Even if her students don’t have the best receptive sign language, she said, her students can still see concrete visuals of what she’s describing.

“In a hearing classroom, you might have kids write notes while you're at the front of the class presenting, but when you're having Deaf children do that, they're taking their eyes away from you,” Gucinski said. “You always have to be knowledgeable of where their eyes have to be. You want to make sure that you always have a clear communication pathway with them.”

(From left to right) Kaitie Gucinski, Amy Hackett and Sarah Norris pose for a portrait April 12, 2021, at the Indiana School for the Deaf in Indianapolis. Jacob Musselman, DN

In Norris’ second grade classroom, she teaches her five students how to write persuasive paragraphs. Because there isn’t always a word-for-word translation from English to ASL, Norris’ worksheets have markings above the English words to show how to express the phrase in ASL.

“Just like a hearing student — yes, they grew up with that language, and they hear that language all the time, but there you'll still hear little kids that say things wrong that are not grammatically correct. The same thing can happen in ASL,” Norris said. “We want to make sure here we are a language school, and we're supporting appropriate language. A lot of it is making sure that they have that full language of ASL because then they can succeed in English. If they're missing grammatical aspects of ASL, then their English is also going to struggle. They need to have a solid ground in one language before they can have another.”

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic Gucinski, Norris and Hackett all wear face shields in their classrooms. Because ASL is an incredibly visual language that relies on facial expressions, Gucinski said, wearing face masks makes it harder for her students to communicate because a sign can have 10 different meanings with different facial expressions.

Students getting her attention has also been difficult, Gucinski said, because in sign language, a common way to get someone’s attention is to tap them on the shoulder, but now she and her students must remain socially distanced.

“I miss hugging students,” Gucinski said. “I miss being able to give high fives and hugs the most. We do elbow bumps, but it's not the same as a good hug.”

To get her students’ attention and vice versa, Gucinski will flip the classroom’s lights on and off, or she will have her students copy her doing the ASL sign for deer so their eyes and hands are ready to move onto the next activity.

“I have students who are so incredibly creative and have just beautiful little hearts and beautiful little minds,” Gucinski said. “I see how they interact with the world around them, how they can problem solve, how they can take a piece of paper, cut it into a multitude of ways and make something completely new without me having to tell them. Their hands on skills are my favorite to witness because I can see the thought processes that are going in their minds.”

This school year, Hackett said one of the school’s biggest focuses is on social and emotional learning because students have been through so much in the past nine months due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

“It was extremely difficult for our students to be home during that time because some of our student’s families don't know ASL,” Hackett said. “They went home to families without being able to communicate to other people and their family members. There is now a big focus on social emotional learning and getting the kids feeling safe and back with the community.”

In the 17 years Hackett has worked at the Indiana School for the Deaf, she said works to get to know her students’ family because she believes it’s a big factor in student success. She attends her students’ basketball, football and volleyball games to let her students know that she cares about them outside of what they’re doing in the classroom.

“When I see my former students come back as adults, whether they come back as teachers, substitute teachers or a parent, that gives me a lot of satisfaction,” Hackett said. “I see lots of my students working at the school. That definitely gives you some satisfaction to see a successful adult.”

The program’s impact

When Steggs initially found out the Nebraska School for the Deaf she had attended was shut down, she was heartbroken because if it weren’t for the residential deaf school, she wouldn’t have learned ASL or be teaching it at Ball State today.

As she continues her second year working with undergraduate students in Ball State’s Deaf/Hard of Hearing program, Steggs said she is grateful her students are not only curious about ASL as a language but that her students also respect the language and recognize its importance.

“I believe [Ball State’s] Deaf and Hard of Hearing program is so important to deaf teachers because with deaf children, they need the visual stimulation. They need American Sign Language,” Steggs said via an interpreter. “All of my ASL was missing in my earlier years, and my social skills suffered as a result. I’m very thankful for that residential deaf school because it really changed my life. I saw deaf role models there, and I thought, ‘Oh, I didn't know I could do that.’”

Contact Nicole Thomas with comments nrthomas3@bsu.edu or on Twitter @nicolerthomas22.

The Daily News welcomes thoughtful discussion on all of our stories, but please keep comments civil and on-topic. Read our full guidelines here.