Elissa Maudlin is a sophomore journalism news major and writes “Abstraction” for The Daily News. Her views do not necessarily reflect those of the newspaper.

I’m standing at the podium. The bright light shining down on my face to illuminate the stage feels comparable to a criminal interrogation. I can’t see the town hall members, but I can feel their eyes judging me. They sit in their seats, waiting impatiently for the opportunity to blaze me with their concerns, fears and judgements about who I am and the life ahead of me. I am vulnerable — like the feeling in your gut when you answer a question wrong in class or when a person in your friend group gives you that look of judgment after you say something personal. I am standing up at that podium like I am naked, have forgotten to shave all of my body hair and am the only one without clothes on. That kind of vulnerability.

For almost all my life, I have struggled with overthinking. Just this last week, my therapist told me my brain is like a town hall meeting — I’m the leader, and my overthinking and anxiety are the town members who go to the microphone and start spewing crazy theories. Although I have never looked at it in that way, it seems like a plausible comparison.

For me, being an overthinker is not some cute phrase in a Tumblr bio. Instead, it could be the one thing taking away my happiness and, in turn, ruining my life.

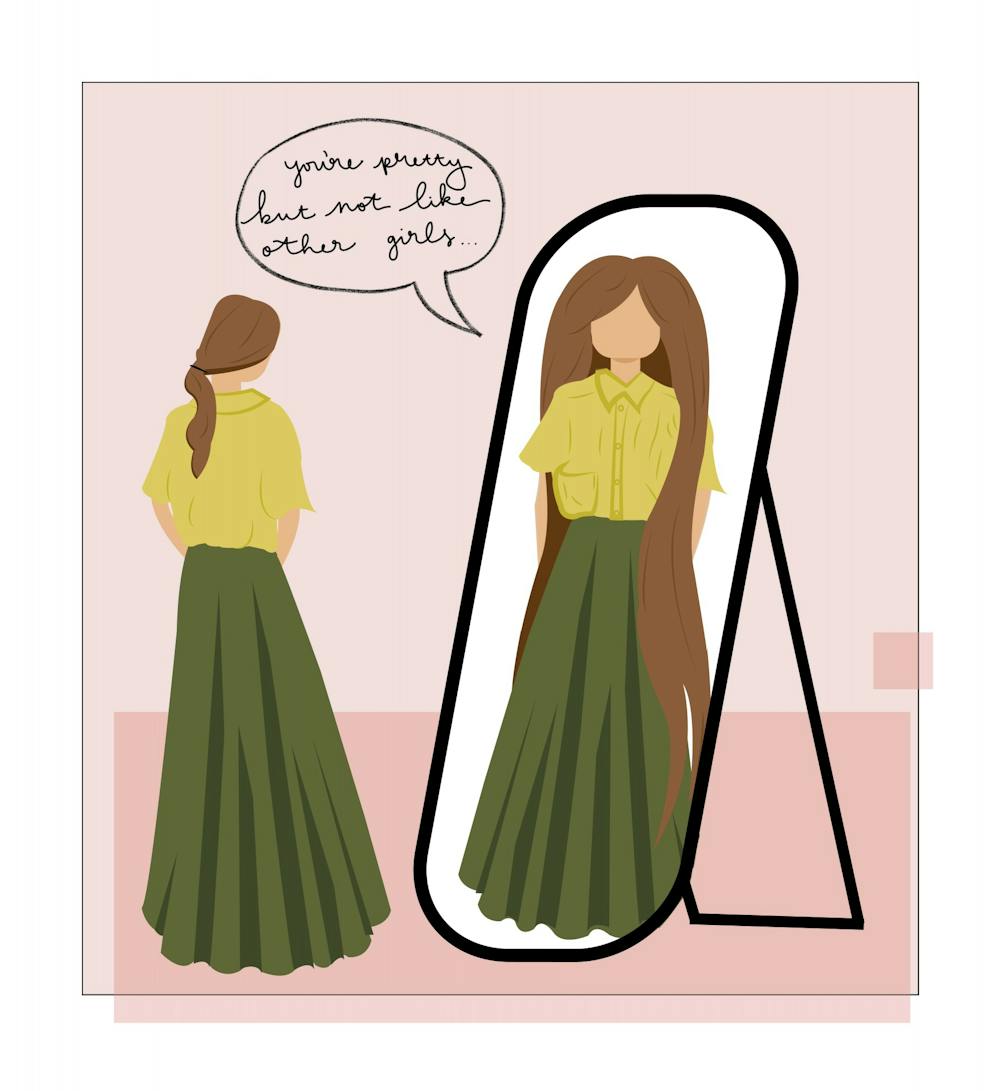

The first of my town members to speak is Debbie. She is like a female version of Bob Ross with long hair down to her knees that waves in perfect symmetry. She wears a long skirt stopping at the ankle and a flowing blouse made of an all-natural material — her bare feet squeak across the floor. Whenever Debbie comes onto the scene, you get the sense of happiness and freedom, but there is an underlying darkness when it comes to her. She is a proponent of happiness but in constant comparison with other people and how they found their happiness. She controls a lot in my life, and most recently, Debbie has shown herself through my ambitions and dreams.

Many are told from social media and good parenting that the world can be an amazing place, full of endless opportunities and fulfilled dreams. For people like me, we set out to find happiness and conquer our ambitions. Debbie wants this for me but unintentionally sabotages it.

As she stands at the microphone and looms over me, she begins to ask her questions like she always does when it comes to my passions.

“Is this your life purpose? Is this the right move? Do you actually like this? Is this actually your passion? Do people want this more than you? Are you taking an opportunity away from someone else?”

Debbie doesn’t want me to pursue things unless she knows they are my absolute passion. If there is a doubt with my choices, she wants to throw in the towel because “How dare I take away something that could have been given to someone else if I don’t know if I actually want it?”

Debbie may have good intentions, but she’s never willing to take a chance. She wants me to be happy, but she constantly compares me to everyone else. She never tries things to see how they go — telling me to find a passion without giving me a means to do so. Debbie is terrified I’ll get stuck but is the number one element in my life that is making that a reality.

As Debbie walks away from the microphone, a tall man with two massive books under each armpit approaches. His name is Arnie, and his dress shoes squeak as he walks up to the microphone. He is dressed in a business suit with perfectly hemmed dress pants, a white button up and an ironed blazer. Slamming the books on the podium, he begins leafing through the pages. He seems harmless. He adjusts his glasses, his smoothed-back hair perfectly set, before addressing all the research he’s done on how I’m an immoral person.

Arnie is like a lawyer prosecuting me, researching everything I’ve done in my life and making implausible verdicts that I have to fight myself not to believe. He doesn’t want to see me hurt other people. Frankly, Arnie isn’t sure if I’m a moral person to begin with. Whenever I do something that could be interpreted badly, even if that isn’t the intention, Arnie starts to question my decisions.

“Maybe you meant to put sunscreen in that person’s wound cause you knew they’d get upset. You’re leading that person on. You meant to look at that attractive person twice because you want to cheat on your partner. You’re a monster, and the only reason people don’t think you aren’t is because they don’t know it yet.”

Arnie tells me I’m a liar, an attention seeker, the worst of the worst. As much as I’d like to say I’m above believing him, I’m not. Arnie sabotages my relationships, makes me second guess text messages and is the primary reason that I think about myself the way I do. It has left me without real romantic relationships because it is easier not to hear Arnie’s arguments and sit in his courtroom. There have been nights of tears, stress and worry over being the monster Arnie thinks I am — a reflection of myself that isn’t the reality. Yet, as he steps up to the podium to talk, I am deeply afraid of him.

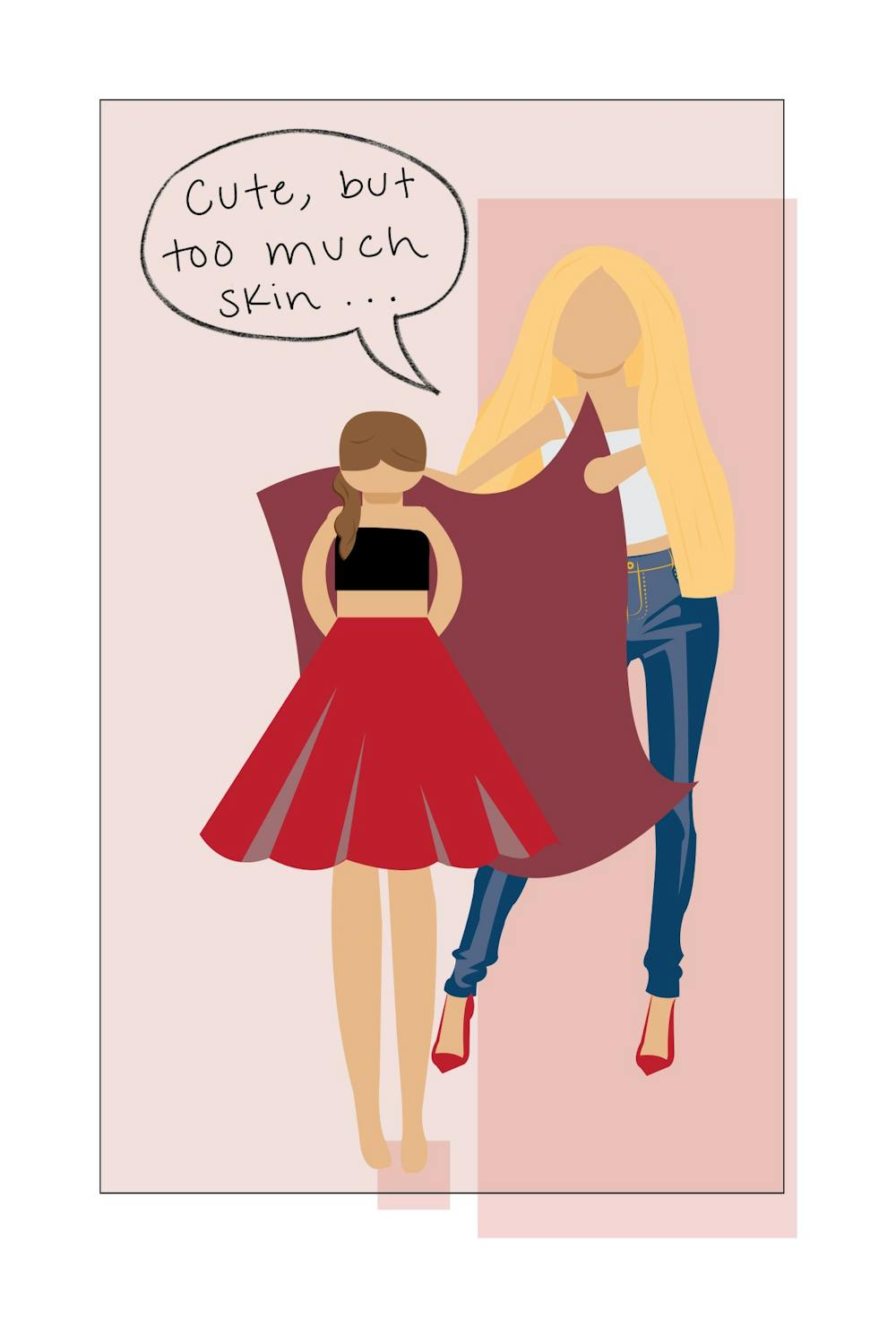

Last to speak is Pelna, the town hall member who constantly underestimates me. Pelna wears the brand-name clothes everyone else wears, and she always has her perfect blonde hair straightened. Without an ounce of originality, Pelna is there to remind me to play it safe and not to speak my mind because she is terrified of judgment. She doesn’t like me doing things that are remotely scary because she doesn’t think I can handle them. If there is a chance to screw it up, Pelna doesn’t want to risk it because she understands shame.

She makes me feel like I am stupid, like I can’t do the things everyone else can. She tells me I shouldn’t get a job working at my dining center because I won’t be good at food service and that I should tell the boss of my summer camp job that I can’t try to be a lifeguard because I’m not a good swimmer.

Pelna constantly underestimates what I can do, and it leaves me with a lack of confidence. Sometimes, she tells me what I’m about to say in class or text a friend is stupid. Pelna watches as opportunities go by, safely tucked in security while dreaming of being brave.

Debbie thinks I’m going to get stuck. Arnie thinks I’m a monster. Pelna thinks I’ll be judged. They come to my town hall to remind me of that.

With every new experience, I am held in this state of being stagnant. If it were up to my town hall members, I’d take the persona of the monster who tries to hurt people, someone who’s going to get stuck in life without a passion, who can’t do anything like anyone else, who would be judged if people knew her vulnerabilities.

But it’s not up to my town hall members. It’s up to me.

If there’s one thing I’ve learned from having anxiety and being an overthinker, it is this: Learn to be uncomfortable.

People talk about recovery like it is easy. In reality, it is exhausting. There are moments when you look at everyone else proceeding with their life, you look at yours, and you just think, “What happened? How did I get here? This wasn’t how I wanted this to go. This wasn’t who I wanted to grow up to be.”

There are times when you feel like you can’t go another day like this. But you wake up the next morning, and you do it again. It happens one step at a time, and even when your brain can’t comprehend doing it again, you do it again until eventually you’re back at your normal — when the overthinking is still there, the anxiety is still there, but you see the light at the end of the tunnel.

It’s about doing the things that scare you. It’s about getting that dining job, doing that swim test to be a lifeguard, saying that thing in class, sending that text to a friend and remembering who we are when a town hall member judges your decisions and morality. It’s about breaking down fears one at a time to show your town hall members there is nothing to be afraid of.

It’s about living, in the best sense of the word.

No matter where you are on the overthinking spectrum, it’s difficult. One of the biggest things I want society to learn is overthinking isn’t something we should look past or trivialize. Overthinking can be detrimental to a person’s future, limiting their opportunities and possibly their quality of life. If our goal in society is to improve quality of life, we need to take over thinking seriously on the societal lens.

I also think we need to be taking it seriously within the personal lens if we are overthinkers. In my own life, Arnie usually disregards what I am going through because it doesn’t seem severe enough or he justifies that, “Other people would be able to deal with my problems better than me. I’m just a coward.” There’s a good chance I’m not the only one who has an Arnie that tells them that. I may not be the only one who has a Debbie or a Pelna. Overthinking can be really difficult, and it is important for overthinkers to acknowledge the strength it takes to deal with it.

As I silence the town hall members and tell Debbie, Arnie and Pelna to back off, I remind myself that this is my town hall, and I gather up the courage, once again, to take control of it.

Contact Elissa Maudlin with comments at ejmaudlin@bsu.edu or on Twitter @ejmaudlin.

The Daily News welcomes thoughtful discussion on all of our stories, but please keep comments civil and on-topic. Read our full guidelines here.