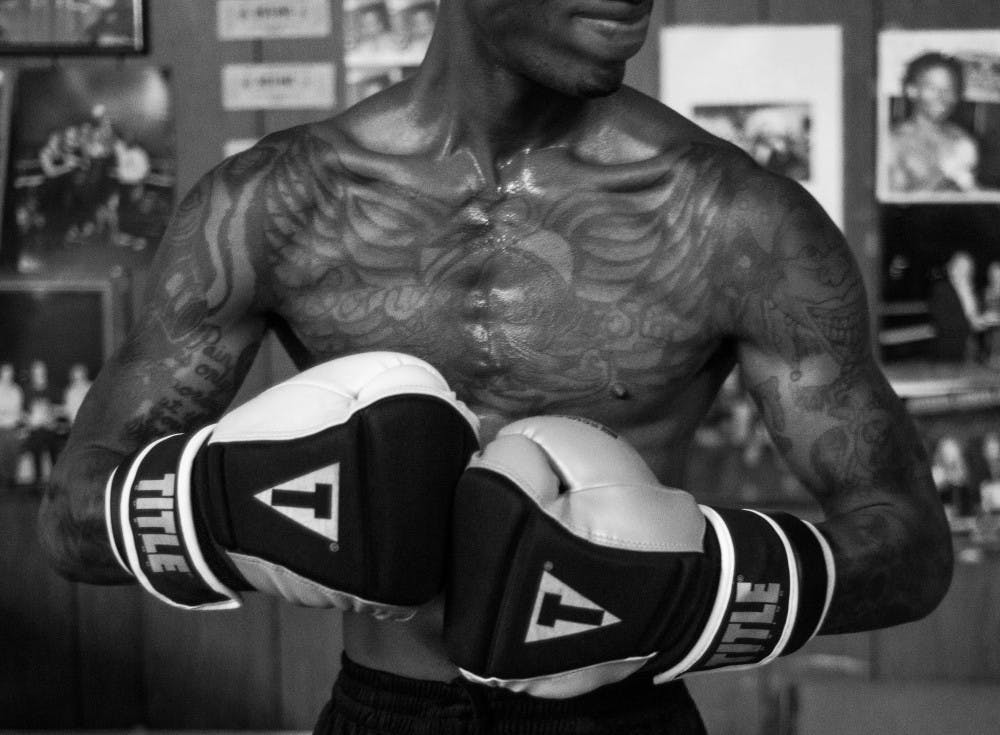

Dodging left hooks in one corner of the ring, David Spikes finagles his way out of his opponents grip, feet bouncing simultaneously to the hip-hop music playing over the speakers.

The dim light projecting over the ring highlights the sweat dripping from his face, off his blue helmet all the way to his worn, white boxing gloves.

“I’m the fastest ever. No one can beat me. No one touch me,” Spikes mutters to himself during fights. “I just carry myself like that and they end up slipping up, bad. I like to get in the guys head because if you can beat them mentally, you can physically. Sometimes I’ll first crack a smile I’ll wave at them. I know they’re going to be mad at that.”

Fighting is enjoyable for Spikes — at least now it is.

But homeless and alone just two years ago, fighting was his only option.

Muncie Pal Club

Just beyond the train tracks that separate the North and South side of Muncie sits the Muncie Pal Club. A one-ring boxing gym that shares a street with a nightclub and a church, holds the capabilities of turning amateur boxers pro. It was by chance Spikes stumbled upon the gym — and the sport of boxing.

“It gave me that purpose again,” Spikes said. “I was able to set goals again and do things to accomplish it.”

Pal Club, which stands for Police Action League, initially created by the police department, has been around for decades.

“The whole idea behind it was to get the police mixed in with these communities that they can lose touch easily,” Steve Douthitt, Pal Club director said. “Boxing is a poor people sport, generally. It doesn’t take much money to get into it.”

While the police presence has dwindled since the clubs beginning, the club goal remains the same.

“This gives a lot of people a chance to pursue a dream,” Douthitt said. “They’re coming in here, working out, it’s positive and they’re around other people.”

Fighting to survive

Spikes self-describes his life journey as a “typical sad story.” He doesn’t cut himself any slack though.

The 20-year-old native of the south side of Chicago was in a dark place when he moved in around the corner from the boxing club.

“It’s been a long journey,” Spikes said. “I’ve been through the most crazy stuff.”

At the moment he discovered Pal Club he was homeless and in a new city.

Spikes initially moved to Muncie with his mother’s husband — the father of his two half brothers. With his mother no longer in the picture and his biological father never being in the picture, this was his family. He thought.

“He [stepfather] treated me like crap,” Spikes said. “He would try everything to break me down. I refuse to let him get in my head and break me down.”

The mental and physical abuse became debilitating for Spikes. He no longer wanted to do anything anymore, even play football, which was his life at that point.

“Having someone tell you you’re nothing you’re constantly hearing that everyday and your whole purpose is to make them proud,” Spikes said. “It takes your ability away.”

At five years old, Spikes’ mother abandoned he and his brothers in their Chicago apartment.

“My mother left me and my brothers to die basically,” Spikes said. “She was gone for like a month or so. It was just God, he told me the correct things to do and me and my brothers managed to survive.”

Spikes lived with his brothers’ grandmother for a few years growing up.

“She developed a love for me,” Spikes said.

A love Spikes is now discovering again at Pal Club.

Boxing family

When he found a passion for boxing at Pal Club, he found something he rarely experienced growing up — a family.

“I’ve created a family because of my boxing. Not being homeless again, I was homeless before I developed a relationship with a lot of people here,” Spikes said.

Those relationships are apparent as Spikes struts through the club high-fiving and conversing with everyone he sees.

“Hey Afro,” Ashley Calhoun says to Spikes as he play-punches her 8-year-old son, Max.

Most parents of fighters come to the Pal Club to watch their kids’ fight.

Spikes doesn’t have family there.

“He’s got no one,” said Rob Calhoun. “He calls Ashley and I mom and dad.”

These people are his family and role models — especially Douthitt.

“I call him pops and everything, he’s really a good figure,” Spikes said. “I call him pops because I don’t have that father figure.”

Douthitt watches Spikes get better every day admiring his work ethic and determination.

“He works harder than anybody else by far,” Douthitt said. “Unbelievable how a guy like that can make it through without getting on drugs and getting in trouble.”

With the support of his boxing family, Spikes was able to get his own apartment in town dropping the title “homeless boxer” to “boxer.”

A new love

Growing up, football consumed Spikes’ life. One of those special athletes coaches demand be on the field for offense and defense — that was Spikes. But the will to fight was always in his blood.

Spikes initially learned to fight after getting repeatedly jumped on the streets of Chicago.

“The way I speak everyone always thought I was soft person and they prey on the weak so everyday I pretty much had to fight,” Spikes said. “A lot of times I would get jumped because a lot of guys couldn’t fight me one-on-one because I was quick.”

It wasn’t until Pal Club that he was able to hone his skills and put them to use. His 6-feet, 132 pound frame aids him in quick movements within his sphere. His style mimics that of legendary boxer, Floyd Mayweather. The rolling shoulder defense is Spikes’ go-to method.

Even though a boxer and enduring multiple blows to the body is imminent, he doesn’t like getting hit.

“I block a lot of movements I don’t like to get touched,” Spikes said. “A lot of guys’ styles is to take a punch. Those are the guys with the short careers.”

Next up for Spikes is the Golden Gloves at the end of the month. One of these days Spikes will become a professional boxer. When that happens he plans to write a book about his life, boxing and his desire to succeed against the odds.

Until then, he keeps fighting.

“No one wants to believe you or try to help you if they do not see a purpose or see desire form you,” Spikes said. “I keep that desire even through the pain; you got to want it.”

Contact Elizabeth Wyman with comments at egwyman@bsu.edu or on Twitter at @_ElizabethWyman.

The Daily News welcomes thoughtful discussion on all of our stories, but please keep comments civil and on-topic. Read our full guidelines here.